Leading the remote work teams of the future

It’s surely a key question on the mind of every manager of skilled employees: how best to manage staff in the ‘new’ era of permanent flexible working arrangements? If you are managing people remotely then is a bit of “managerial rigour” the best way to keep everyone on their toes and highly productive?

After reviewing 160 studies of different leadership styles, I have three words of advice: back your people. Actually, the key three words are ‘autonomy supportive leadership’.

Bosses who tightly control their staff are likely to incite anti-social behaviour that will sabotage the entire teams’ performance.

By contrast leaders who offer clear explanations, invite input and welcome staff-initiated choices as to how to tackle tasks are likely to build collaborative, high performing teams with a prosocial culture.

Controlled v autonomy supported leadership

Research my colleagues and I conducted over the past 3 years explored two contrasting leadership styles. Specifically, we examined the effects of these two contrasting styles on individual’s propensities toward cooperation, collaboration, and helping behaviours (i.e. “prosociality”), and also withdrawal, undermining or sabotaging behaviours (i.e. “antisociality”). We wanted to find out how these contrasting leadership styles impacted individuals’ pro and antisocial behaviours, which has important implications for high performing teams.

The two leadership styles we explored were “controlled” and “autonomy-supportive” leadership. Controlled leadership is where a manager uses extrinsic incentives to motivate the individual or team. These typically take the form of “carrots” and “sticks”. Examples of carrots include social recognition (staff awards), financial incentives (bonuses) and status (promotions, new titles). Sticks include withholding new opportunities, bonuses and promotions, the use of public performance metrics (e.g., sharing individual performance metrics with a team), and more subtle forms of coercion and pressure.

In contrast, “autonomy-supportive” leadership is where the leader provides clear explanations for why a task or project matters, invites input wherever possible, provides choice as to how the task gets done, and offers constructive support in addressing obstacles as they arise.

Leading the pro-social way

Our meta-analysis found contrasting effects of these two styles on individuals’ likelihood to act in prosocial and antisocial ways. We found that controlled leadership was linked with more with-holding of information, less discretionary effort, and even efforts to sabotage and undermine others. We found this across a range of situations, including in companies, in schools, among health professionals, and even among parents.

In contrast, we found that autonomy supportive leadership is consistently associated with more collaborative, cooperative, and help-giving behaviour. Again, we found this across a range of countries and social situations (e.g., business, education, and healthcare).

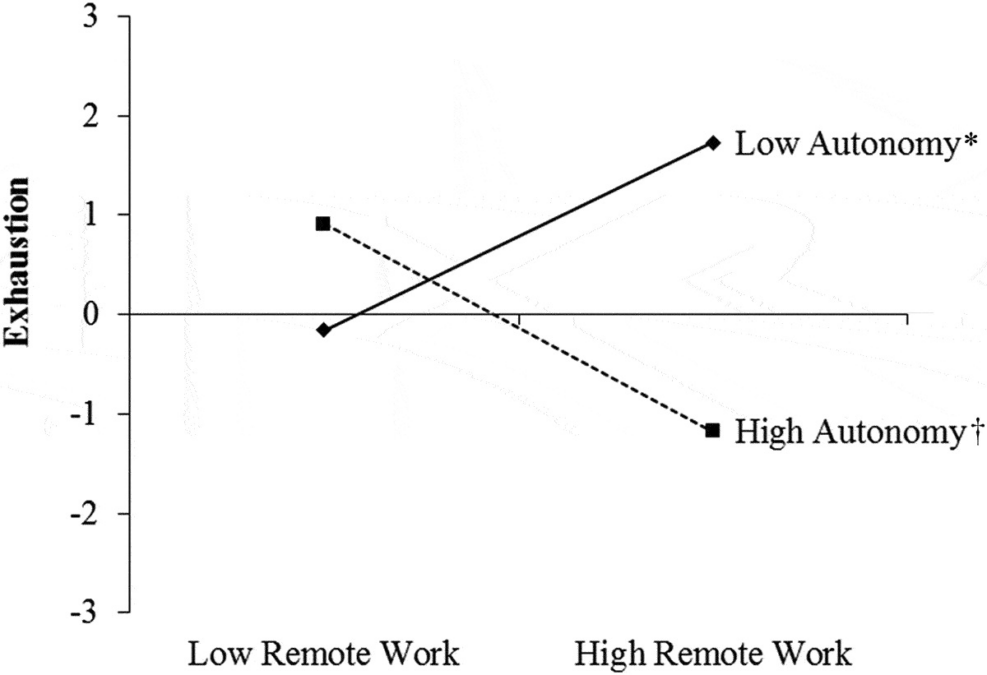

Our findings are consistent with other studies that have shown that when staff who work remotely experience greater autonomy, they also experience greater job satisfaction, productivity, and less job stress and intentions to quit. And these effects are compounded in a remote work environment. For example, a study of engineering, tech and local government employees in the US found that in remote settings, the benefits of autonomy in lowering employee exhaustion more than doubled, relative to a face-to-face setting.

Rather than seeing flexible ways of working as a threat to the business, managers and executives need to ask themselves: how do we design work arrangements and adapt our leadership methods to take maximum advantage of the opportunities flexible work provides?

Incentives – not so much

Our study found that a key to solving this puzzle is to think carefully about the leadership style managers of flexible teams use. For businesses that want to build highly collaborative, responsive and supportive teams, we found that autonomy-supportive leadership is key. Also key, is to avoid relying on leadership strategies that favour extrinsic rewards and incentives.

Based on my own research and experience working with remote teams, here are some practical examples of what of autonomy-supportive leadership looks like:

- Get clear on why a project or task is important and needs to be done and communicate this clearly. Take the time to ensure your team understand and have their own sense of the “why” for what they are working on. Different people will have different reasons for why a project or task matters, and it’s important that they feel clear about that, if you want a highly collaborative, prosocial team environment.

- Look for opportunities to provide agency and choice for staff, even when it feels uncomfortable. Examples include providing as much flexibility as possible as to when and how work gets done; seeking your team’s ideas and input on decisions; providing opportunities for fun and social connection.

- Provide regular feedback to staff that is authentic. Positive feedback and reinforcement needs to far outweigh negative feedback, and this is amplified in a virtual setting. Feedback, whether positive or negative, needs to be genuinely given and regular.

- If you want to build a collaborative, high-trust environment with a virtual team, minimise the use of carrots and sticks to motivate staff, and focus instead on acknowledging people’s initiative, effort, and ideas. Virtual work can feel ‘transactional’ and task-focused at times. Managers need to nourish their teams’ sense of shared purpose, connectedness and fun, if they want to build a highly collaborative, committed virtual team.

As leaders look to set their teams up for success in the world of ongoing hybrid work, our research says that using autonomy-supportive approaches will reap big benefits, in terms of building a culture of collaboration and trust.

This is part of a series of insights related to Coronavirus (COVID-19) and its impact on business.

Image: Sigmund

James is a Senior Lecturer (Teaching and Research) in the in Work and Organisational Studies discipline at the University of Sydney Business School, where he teaches management and leadership.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.