Sydney Business Insights

Hybrid work: the 9 things we have learnt

After the pandemic-induced experimentation with new forms of work – here is a checklist of nine things we have learnt about hybrid working (and what is, and isn’t, working).

1. Hybrid is not one thing

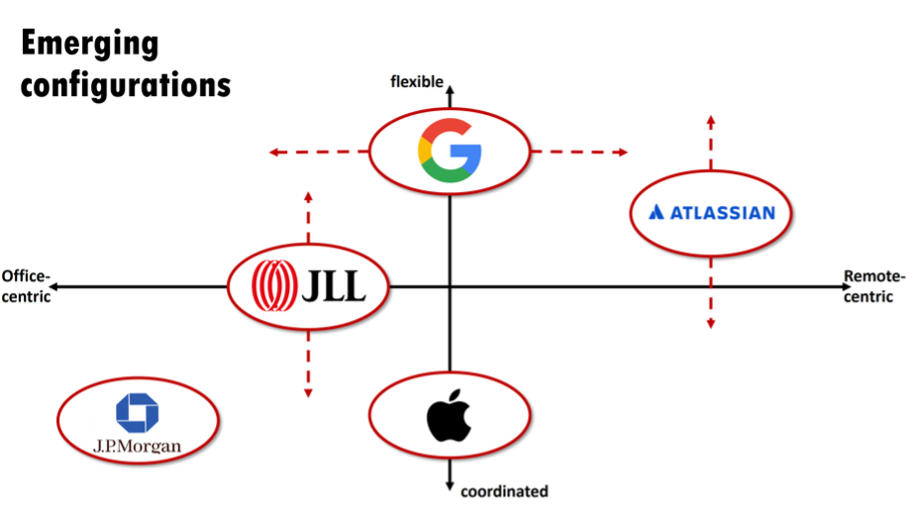

By now companies have settled on different models – from Goldman Sachs ordering all staff back to the office full-time to Atlassian’s, ‘you do you’ attitude, we see different models on the spectrum between heavily office-centric ways of working, and those that favour remote approaches.

At the same time, some companies leave it up to individuals or teams to self-organise how and when they work. Others, like Apple, are a bit more hands-on to make sure their teams coordinate when they work face-to-face together, to harness the creativity of in-person contact. With this many options, the only necessary rule is – organisations need to clearly define what they mean by hybrid.

2. Individual inequalities

Our experience of hybrid work is not the same. About 61% of bosses report they are ‘thriving’ in hybrid work, while less than 40% of those without decision making power feel the same level of positivity about their working arrangements. Another difference between the ranks is the 74% of executives who say they get to decide their working schedule whereas only 24% of junior staff have the right to nominate where and when they work.

Gender differences are also in place: according to a McKinsey study, 61% of male employees were offered remote employment compared to only 52% of women.

The point is we should not average things out. ‘False’ averages hide the very real difference in realities when it comes to seniority and gender. Finally, a forgotten class of workers are the immunocompromised and people with rare diseases: organisations have shown they can come to terms with flexible working arrangements at scale – so let’s not retreat into inflexibility for people who might need this on an ongoing basis, at least as long as the virus still poses a threat to them.

3. The productivity paradox

Productivity is up and down at the same time: that is to say, productivity is up for corporations and down for individual workers. Simply put, productivity is output divided by input. As organisations might measure output per worker, productivity in hybrid work might have gone up. But for workers, their input is time, which can quickly render the equation negative, as people are putting in longer hours (8% a day according to The Bank of England) to the benefit of their organisations but not the worker.

In simple terms commuting time has become working time – although the economist for the Bank of England crunching this set of data confessed that for him the lack of commute was offset by the time spent answering the door for Amazon deliveries.

4. The commute is not all bad

Pre-pandemic studies showed commuting was a twice-a-day negative in people’s lives: an extra 20-minute slog in the traffic was perceived on average equivalent to a 19% pay cut.

Well – now that ain’t necessarily so.

Commuting (of a reasonably short duration) is the soothing ‘switch off’ time between home and work that people actually enjoy. Pre-pandemic research into a concept known as ‘boundary theory’ showed we all host multiple selves and the commute between home and work is an effective way of facilitating a physical and psychological shift between our work and our domestic selves. Indeed some people are re-creating this in-between zone with improvised transition routines (dressing up for the morning Zoom, shrouding the work PC in a cloth after logging off for the day.)

5. Zoom fatigue is real

A video wall of faces is psychologically more draining than in-person meetings.

With no opportunity to shift focus we rely on the face alone to decipher non-verbal cues which is considerably more demanding than being able to ‘read’ an entire body for meaning.

On top of this, back-to-back Zoom meetings don’t offer the mental or physical respite that walking between meetings and occupying different spaces naturally grants.

What can we do? Instead of scheduling yet another Zoom consider going old-school with a phone call. Or make the time and effort to meet in person, take a ‘walk with me’ mobile meeting. And don’t subject everyone to an hour-long meeting – dial people in for the 10 minutes they actually need to attend, a good practice for meeting in any form.

6. Social capital needs care

Networking actually needs the office. No one ever gets casually ushered into a Zoom session to be introduced to another person. By contrast there are lots of “hey – meet Zonk, he’s new” opportunities when people are milling around the workplace or the coffee shop. Serendipity matters in life and work but it has to be helped to happen. People who work remotely have fewer collaborators and certainly fewer new associates.

The less time we spend physically together the less we engage with each other, the weaker our interpersonal ties become and our networks shrink. Which in turn leads to a weaker social fabric of the organisation as a whole.

7. The loneliness of the hybrid worker

Having ‘chemistry’ is not just an expression. Neuroscience research has shown that only in-person interactions trigger certain types of physiological and neural responses, that engender trust. And the digital channels we use to engage actually disrupt those responses. Meaning your brain is not producing the necessary chemicals you naturally feel when you are in the presence of other people.

The point is not just to go to the office to work alongside others – you need to engage with them, ask them how they are doing. Put some chemistry back into the situation, which is why some companies favour the coordinated approach to hybrid work, to make sure that teams who work together, actually work together.

If regular office gatherings aren’t happening, then building meaningful rituals could help with the teamwork: put in place strategies that could help with early detection of issues that if left unattended could become much more serious.

8. Leave it to the team

Turns out organisations that leave up to the ‘collective’ to decide what are ‘office’ days achieve a similar attendance than if management mandates the days. The logic of the group also helps create a better office mood. So, leave it to the teams to coordinate (but not everyone individually).

9. Short-term gain, long-term pain

We are calling it – the social capital that has been built up over decades is now being depleted. The social foundations of our organisations are crumbling, slowly at first, but this is the ultimate cost of hybrid and remote work, and the lack of in-person contact.

In the 1900s ’scientific forestry’ principles developed by German farmers saw the mass planting of the Norwegian spruce tree (known for its hardiness and rapid growth). The spruce became the ‘bread and butter’ of commercial forestry in Europe. Initially it produced such outstanding results this mono-crop process was adopted in North America, India and Burma. However after a few crop cycles the total lack of a natural ecosystem caused the forests to die off. It became clear that the spruces had only thrived on the fertile soil left behind by the old forests, without however replenishing it.

The excitement around not having to drag yourself into the office, the temporary uptick in productivity – these might not be the best indicators of a thriving workplace environment in the long term. If you are not physically in the office engagements, personal and professional, do not naturally flourish.

Just as forests fail if the soil is not nourished by ‘unprofitable’ elements, a thriving work environment needs organic (if unmeasurable) features to nurture collaboration.

Fridays are doomed

And finally – Fridays are doomed, Thursdays are the new Fridays. Even if a company has not opted for a 4-day working week, Friday increasingly is a dead zone: between 60 – 88% of workers don’t swipe in on Fridays. And for the home toilers, some organisations like Citigroup and KPMG have declared Fridays ‘no Zoom’ or ‘no camera’ days.

So – get back to the office at least part-time, figure out when with your colleagues, take care of those who don’t or can’t turn up and remember that to Zoom is not the entire picture, there is a whole other level of engagement outside of the screen. You’ll thank us in the long run. And you’ll meet us in the coffee shop.

Listen to more about the future of business on The Future, This Week with Sandra Peter and Kai Riemer.

Sydney Business Insights is a University of Sydney Business School initiative aiming to provide the business community and public, including our students, alumni and partners with a deeper understanding of major issues and trends around the future of business.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.