Brands that increased their marketing spend were able to grow market share faster

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the landscape for many companies. It’s seen some brands have a sudden increase in demand (booming brands), others a decline (declining but surviving brands), and some brands have unfortunately had to temporarily close their businesses (hibernating brands).

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the landscape for many companies, forcing them to shift the tone of their brand marketing.

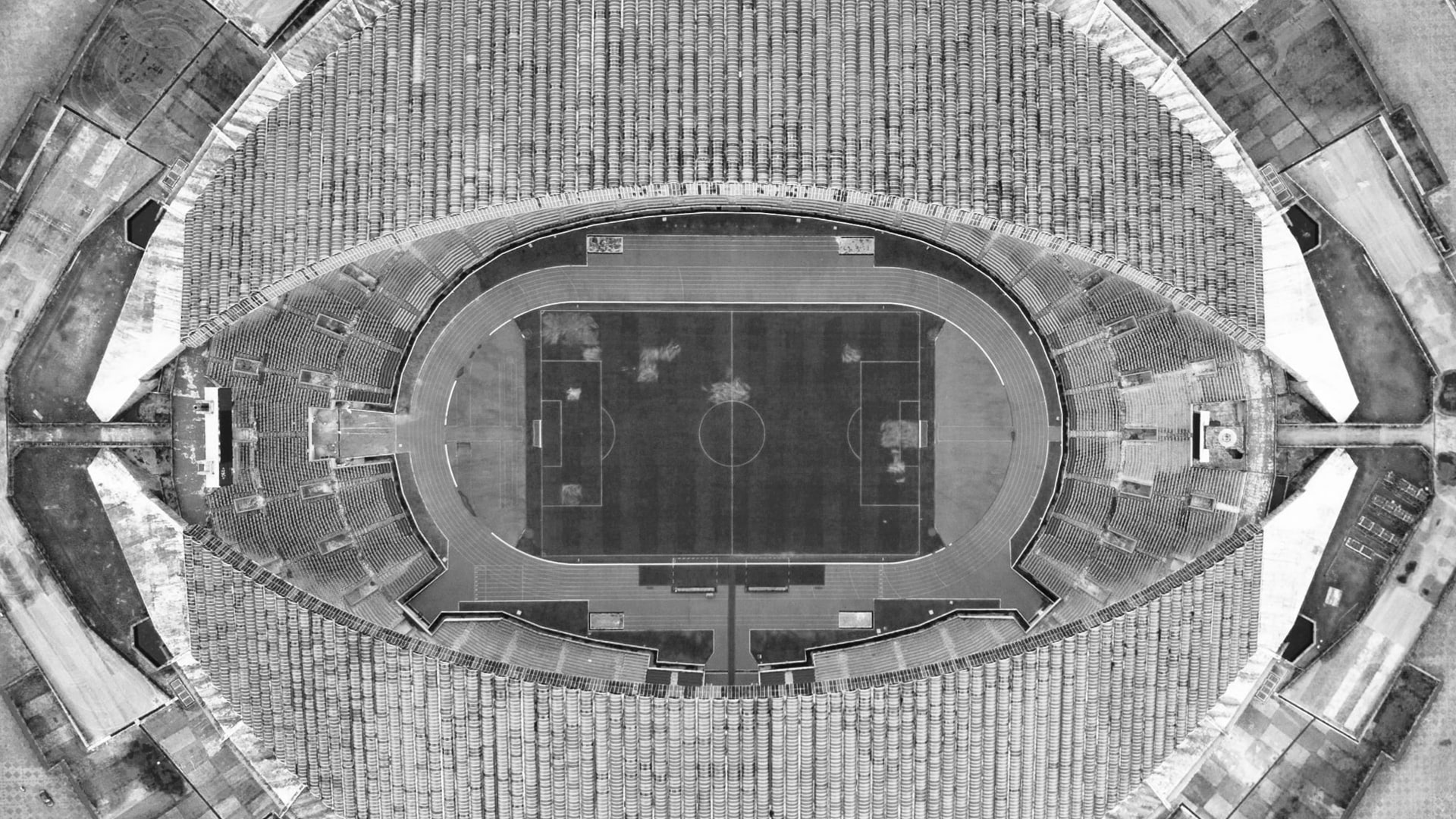

In happier days key football brands employed a stereotypical TV ad format: big hits and tackles, cheering fans packed into stadiums, a war-cry-like tagline and inspiring music track.

But these images will not be as relevant or appropriate in a post-pandemic world. The NRL has moved quickly, announcing it is moving away from its “Simply the Best” TV ad for its season restart. Instead, the upcoming campaign taps into “virtual tribalism”, encouraging fans to watch the game at home on TV while the social distancing rules remain in place. The code has recognised early that rebranding is essential.

Research from previous downturns shows brands that increased marketing spend were able to increase market share three times faster during the recovery period.

During the depression, Kellogg’s maintained advertising spend while its main competitor cut spending, leading to Kellogg’s dominant market position for decades. In the mid-1970s recession, Chevrolet increased advertising spend while Ford cut back, leading to a two share-point market share swing.

But using the right levers and message is crucial.

Does the changing business environment require additional R&D, new product development or improvements to products/service, upgrades to digital platforms, re-evaluation of distribution models, improvements to customer experience, a change of pricing models, a rethink of marketing operations, an increase in advertising spend versus competitors or, as in the case of hibernating brands, a re-look at the ads themselves?

During the GFC, Amazon continued to invest in product development, launching Kindle at the end of 2009. During the SARS outbreak, with consumers isolated at home, two Chinese companies famously pivoted their businesses online: Alibaba with Taobao and Jingdong, now JD.com.

History favours the brave.

And for many consumers of these brands, who have been living for many weeks in home isolation, it’s meant a sudden change in their needs and behaviours, as well as their expectation from brands.

As marketers plan for a recovery from COVID-19, hibernating brands need to carefully map out the steps required to re-launch their business. As part of that, they will need to reset their marketing objectives and KPI’s, and determine which marketing levers to initially unlock, with a likely smaller budget than they had prior to COVID-19 breaking. And many will also be forced to shift the tone of their brand marketing.

Take key sporting brands such as the NRL and AFL. Football codes have employed a stereotypical television ad format: big hits and tackles, cheering fans packed into stadiums, a war-cry-like tagline and inspiring music track.

But much of this will not be as relevant or appropriate in a post-pandemic world. The NRL has moved quickly, announcing it is moving away from its “Simply the Best” TV ad for its season restart.

Instead, its upcoming campaign taps into “virtual tribalism”, encouraging fans to watch the game at home on TV while the social distancing rules remain in place. The code has recognised early that rebranding is essential.

The opportunity in planning for a recovery for booming brands, and declining but surviving brands, is around smart marketing investment and planning. Research from previous downturns shows brands that increased marketing spend were able to increase market share three times faster afterwards. But you need to use the right levers.

Does the changing business environment require additional R&D, new product development or improvements to your product or service, upgrades to digital platforms, re-evaluation of distribution models, improvements to customer experience, a change of pricing models, a rethink of marketing operations, an increase in advertising spend versus their competitors or, as in the case of hibernating brands, a re-look at the ads themselves?

Brands that maintained or invested more in advertising during the 1991 recession had a five-year sales advantage of 25 per cent over competitors that did not. However, the initial reaction of many marketers during the shutdown has been to do the opposite, as consumers are spending more time online and watching TV.

According to media agency Initiative, Australian free-to-air TV ratings during lockdown are up about 10 per cent on the corresponding period the year before. Yet TV advertising spend was down 8.2 per cent in March according to SMI.

A recent US survey showed 41 per cent of brands have decreased broadcast TV advertising. However, many are taking advantage of the increased consumer traffic online: a US study at the end of March showed 48 per cent increasing their advertising spend on Facebook, and 37 per cent on Google. Global advertiser P&G announced it would continue to invest in advertising to maintain brand visibility. But Coca-Cola announced it would cut spend because it was seeing limited effectiveness with consumers in home isolation and unable to access its products in restaurants, pubs, cafes and tourism venues.

There are well-recorded examples of many brands successfully increasing or maintaining their advertising during downturns, and seeing sales increases for many years following the recovery period.

Leading into the 1990 recession, Nescafe relaunched its Gold Blend brand, doubling market share and increasing sales by 60 per cent. During the depression, Kellogg’s maintained advertising spend while its main competitor cut its spend, leading to Kellogg’s dominant market position for decades. In the mid-1970s recession, Chevrolet increased advertising spend while Ford cut back, leading to a two share-point market share swing.

In World War II, many brands such as General Motors, Coca-Cola and Hershey quickly rallied behind the war effort, extending their businesses’ production and distribution capabilities, which meant they were well positioned to expand globally at the end of the war.

Through the early 2000s downturn, Apple and Sanofi invested heavily in R&D against the norms of their competitors, with Sanofi winning market share and Apple launching the successful iTunes and iPod Mini in the years immediately afterwards.

Others, such as Sony, felt the adverse effect of pulling back on R&D, capital expenditure and talent as they shored up short-term profits. Sony recorded double-digit sales declines on average across the next three years.

During the global financial crisis, Amazon continued to invest in new product development, launching Kindle at the end of 2009 and during the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak, with consumers isolated at home, two Chinese companies famously pivoted their businesses online: Alibaba with Taobao and Jingdong, now JD.com.

At the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, Master Kong, an instant noodle and drinks company, focused on tracking the reopening plans of retail outlets and adapted its supply chain accordingly. The company was better prepared for the recovery period and was able to ensure supply of stock for three times the stores its competitors were able to.

To ensure they’re optimising productive marketing spend, booming brands naturally doing well from COVID-19 should also consider holding back short term promotional spend and diverting it into brand spend or customer experience improvements. Declining but surviving brands should consider allocating funds into peak sales periods to make the most of the marketing spend they have available. And whilst many hibernating brands can’t follow suit due to the minimal marketing funds currently at their disposal, they can still work hard to out-position their competitors through their owned and earned media channels.

There are obviously many other marketing options to consider in these complex times. One thing that is clear for all brands, is that smart marketing that better positions brands for emerging into recovery, pays longer term dividends.

This article was originally published in The Australian’s The Deal Magazine. Read the original article.

Note: rights to this article belong to the original publisher, The Australian’s The Deal Magazine. please contact them for permission to republish.

This is part of a series of insights related to Coronavirus (COVID-19) and its impact on business.

Image: Fahrul Azmi

Thought leader, marketer and board director, Andrew Baxter is the Senior Advisor at KPMG's entrepreneurial Customer, Brand & Marketing Advisory business, a Senior Advisor at BGH Capital, as well as the Adjunct Professor of Marketing at the University of Sydney, and a Non-Executive Director at Australian Pork and Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.