Sandra Peter and Kai Riemer

Tourism on Corona Business Insights

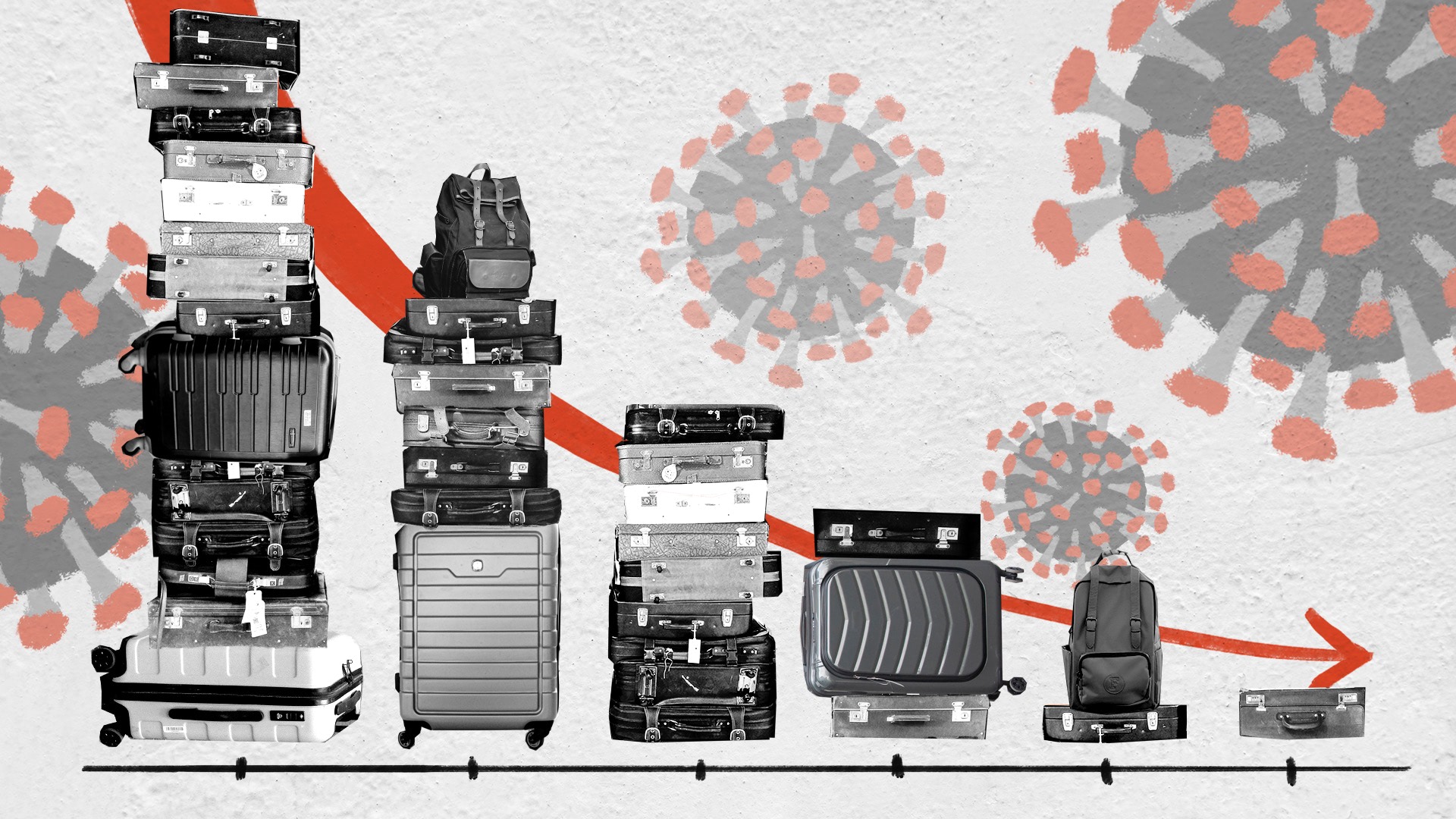

With travel ground to a halt tourism has the opportunity to rethink its ways. As the world reopens will recovery lead to more sustainability or will old patterns return?

As COVID-19 sets out to change the world forever, join Sandra Peter and Kai Riemer as they think about what’s to come in the future of business.

Shownotes

UN World Tourism Organisation estimates earnings from tourism might be down 80%

Does COVID-19 spell the end of tourism

What happened on Santorini when the tourism stopped

Our discussion on scientific research opportunities during COVID-19

Tourism operators say things will look very different as Australia emerges from coronavirus

The Federal Government will spend $233 million on tourism and infrastructure projects

With love from Aus ❤ (yes it’s not in the podcast but we like it)

This episode is part of a podcast series covering what COVID-19 will mean for the business world, where we look at the impact on the economy, businesses, industries, workers and society. This is part of our ongoing coverage of the impact of COVID-19 on the future of business.

Follow the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts. You can follow Sydney Business Insights on Flipboard, LinkedIn, Twitter and WeChat to keep updated with our latest insights.

Send us your news ideas to sbi@sydney.edu.au.

Dr Sandra Peter is the Director of Sydney Executive Plus at the University of Sydney Business School. Her research and practice focuses on engaging with the future in productive ways, and the impact of emerging technologies on business and society.

Kai Riemer is Professor of Information Technology and Organisation, and Director of Sydney Executive Plus at the University of Sydney Business School. Kai's research interest is in Disruptive Technologies, Enterprise Social Media, Virtual Work, Collaborative Technologies and the Philosophy of Technology.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.

Transcript

This transcript is the product of an artificial intelligence - human collaboration. Any mistakes are the human's fault. (Just saying. Accurately yours, AI)

Intro From the University of Sydney Business School. This Sydney Business Insights.

Sandra And this is Corona Business Insights. I'm Sandra Peter.

Kai And I'm Kai Riemer.

Sandra And with everything that's happening, it's been difficult to understand what COVID-19 might mean for the business world. So in the series, we've been unpacking its impact on business, the economy, industry, government, workers and society and looking at the effects of the pandemic.

Kai And this podcast is, of course, part of a larger initiative by the University of Sydney Business School. Our COVID business impact dashboard is a living initiative which we constantly update with insights and resources from academics, from industry experts, Nobel Prize winners, and movers and shakers.

Sandra And you can find all of these resources online at sbi.sydney.edu.au/coronavirus.

Kai And today we talk about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism.

Sandra Obviously, tourism is fully reliant on people being able to move around from one place to the other, and it has undergone the most stringent and longest lasting restrictions. And it's likely to be one of the sectors that suffers the most from this pandemic. And let's remember that one in 10 jobs around the world depend on tourism. Hence, the impact that COVID-19 has had on the sector is both far ranging and long lasting.

Kai And so we will take a look at the impact that the pandemic has had on tourism. But quite analogous to the episode we did on the fashion industry, for tourism as well this unprecedented crisis and these stop to most, if not all activity in the sector presents an opportunity for self-reflection and potential change because the sector is not without problems.

Sandra But let's first have a look at the impact because it's been quite severe. The United Nations World Tourism Organisation estimates that earnings from tourism around the world will be down by about 80 percent this year compared to last year. And last year's figure was about 1.7 trillion dollars around the world. And they also estimate that up to 120 million jobs could be lost.

Kai And for Australia the immediate numbers don't look that bad, because the Australian financial year ends mid-year, but it is still down by 16 percent on the year from 2019 to 2020. But more importantly, because of the relevance of tourism for Australia as an economy, the drop in activity in tourism will translate into a .7 percent drop in GDP for the calendar year of 2020 alone.

Sandra And many countries around the world are in similar situations, in Europe tourism accounts for about 13 to 15 percent of the GDP of countries like Italy and Spain. But also with places like the Greek islands, for local economies like Santorini it's over 90 percent of its income. And other holiday destinations like Zimbabwe and Botswana are seeing up to 30 percent of their GDP potentially disappear.

Kai And while these numbers are sobering and the economic fallout from the stop in tourism activity is quite severe, this drop in activity has also come with an interesting by-product. Places like Santorini or the city of Venice, which are usually bustling with tourists and are quite overcrowded this time of year, experiencing for the first time in decades. What a summer day would be like where streets are, you know, half empty, where locals regain a sense of normalcy, where wildlife returns to the cities. And we've mentioned this in our previous episode on science opportunities, where we talked about how this presents research opportunities, but it also presents opportunities for locals to reconnect with their places. When the bus loads and ship loads of tourists do not flood into their cities.

Sandra Yes, and places like Santorini do highlight that paradox. Whilst streets are now empty, so Santorini is home to about 15000 people and it usually gets about two million extra people from tourism, mainly from cruise ships, with day-trippers who spend the day and clog up the streets on the island. They also bring about 90 percent of Santorini's income. So the question then is does the pandemic allow us to rethink how we do tourism and find more sustainable ways to do it?

Kai So the problem that places like Venice and Santorini and many other beautiful places around the world have is one of over-tourism. While at the moment people are suffering from no tourism, on a normal summer's day, Venice, for example, suffers from way too many tourists. There's no research which has pointed out that the intake of tourists of about. Three million visitors a year exceeds what's called the carrying capacity of people that the city could take in by about 10 million. That's the capacity at which point the environment, the infrastructure, suffers damage and decay. So the question is, now that tourism has halted, can tourism come back to more sustainable levels? And what would that take?

Sandra And let's remember that for certain places around the world, the tourists that come in and do damage to infrastructure or to natural environments, in the case of more exotic locations, often do very little to contribute financially towards the upkeep of those places for people who come in on cruise ships. Those cruise ships do very little to upkeep the local economy. They're incorporated usually in tax havens overseas. And the people who get off them and spend the day in the city are best than the buying a few souvenirs and maybe a meal, but do very little.

Kai You know, they might not even spend money on a meal because they might get a daypack from the boat and the souvenirs that they buy, they're produced overseas, not locally. So the contribution of some of this tourism that happens to the places that they visit, the assets that they use, the natural beauty that they enjoy is very limited.

Sandra On the other hand, attempts to do tourism quite differently, more or less high end tourism like we've seen in many places in Africa where people spend a significant amount of money to experience exotic locations, contributing up to fifteen hundred dollars a day to national parks to see gorillas, for instance, have led to an over dependence on these tourists. Once income halts is not only the livelihoods of people who are supported by that income, but also the protection of natural habitats and of endangered species that it's also reliant, in most cases, up to 80, 90 percent on income derived from tourism.

Kai So what we're saying is that tourism is really a two-edged sword. On the one hand, tourism contributes to pay for the restoration of buildings and the preservation of the architecture in places like Venice. It pays for the conservation of wildlife in many places around Africa. It lifts people out of poverty and provides employment. But on the other hand, it also contributes to environmental destruction in the cases of Venice, where there is over tourism. It might contribute to the destruction of the very city that tourism is meant to protect. It also drives people out of the cities in Venice. In the last 30 years, citizenship has dropped from about 180000 people to about 50000 people, while visitors have gone up from one million to 30 million per year. And it also distorts local development in many places around Africa and Asia, where people give up agriculture and other practises to go into tourism and then become dependent on tourism, which becomes painfully obvious now that tourism no longer contributes.

Sandra Looking at the ongoing effects of the pandemic, we must acknowledge the time it will take for this particular sector to recover whilst concert venues and galleries might reopen and get people in the next day. It's estimated that tourists will actually take, on average, more than a year to return to these places. And that's based on what we know from previous financial crises, from world changing events like 9/11 or the previous SARS outbreak. So what can we do whilst in lockdown? And many places, including Santorini that we've mentioned before, have taken the time to rethink infrastructure around the island. In Australia, the federal government said they will spend about 233 million dollars on infrastructure projects, around five of our big natural attractions to be ready for when travellers return. But longer term, this moment might also allow us to rethink the type of tourism that we want to return to these places.

Kai And so we want to make the distinction between those types of tourism, the eco-tourism in places like Asia and Africa, and also the kind of city tourism in congested cities like Venice or the island of Santorini or indeed Dubrovnik, which we've mentioned on a previous episode of The Future, This Week, which has benefited, but then started to suffer from the influx of people who are interested in the Game of Thrones scenery of the city. So what can those cities do? Now, one idea is to actually change the makeup of tourism that comes through these cities from less day visitors to coming by bus or cruise ship, which do little to sustain the city, but add enormously to the traffic and waste that is produced during a typical day in those cities, to more overnight stays which leave way more money, they contribute to the local economy because they have dinners and breakfasts. They actually pay for their overnight stay, they pay tax. And taxes is really the key here. Ironically, or not helpfully, many destinations tax overnight guests, because the tax is attached to the hotel stay and is also being collected by hotels through levies and tourist taxes disincentives rising. Exactly the kind of tourism that cities want more of. Whereas people who come in by bus or come in by cruise ship leave very little in the way of contributions. So maybe a rethink is needed where maybe docking fees have to go up quite significantly to make it more expensive for cruise ships to dock, maybe driving away a few cruise ships, having less people about more income. There's an interesting example from Rwanda where the fee that the Rwandan government collects for spending an hour with the local gorilla population has doubled from about 700 to fifteen hundred dollars, which has driven down visitor numbers from 22000 to a more sustainable of 15000. But at the same time, increased revenue by four million dollars. So maybe a rethink in incentives might be a key.

Sandra While in the long run, tax incentives are really important to change the underlying makeup of the tourists that visit an area towards more sustainable types of tourism, what is really important in the first instance is to get people back to some of the places that are now fully dependent on tourist income, places like Africa. And incidentally, it might be that small scale tourism, small groups of people might be easier to bring back to these destinations. However, the economic reliance on tourism might also mean that many of these destinations will now severely cut the prices in an attempt to bring people back sooner.

Kai So while many destinations will be interested to bring back more sustainable, that often means more high value, tourism to their destinations. And that is certainly something that is really important in those places where eco-tourism contributes to the conservation of wildlife. The economic fallout from the pandemic, the economic crisis might mean that tourists will be more price conscious. And the fact that many destinations around the world will compete for getting a share of those first tourists that are coming back also means that there might be an effect that drives prices down. So we're now presented with this conundrum that prices might drop. People might be more price conscious while in the long run these destinations might want to bring back a different kind of tourism. So it would be really important to manage the transition, the bringing back of tourism in a way that achieves both goals, a short term sustainability coming out of the crisis to provide income, but also in the long run to not end up with the same kind of over tourism that any of these places have suffered from.

Sandra And this is where we want to leave it today. This has been Corona Business Insights.

Kai Until next time. Thanks for listening.

Sandra Thanks for listening.

Outro From the University of Sydney Business School, this is Sydney Business Insights, the podcast that explores the future of business.

Close transcript