Mengyu Li and Arunima Malik

The footprint of food miles – we need to start counting

A regular bar of delicious hazelnut chocolate may slip easily into your pocket – but within that tempting package sits a significant carbon footprint.

It’s likely the hazelnuts were grown in Turkey and harvested using a machine imported from Germany. The cocoa butter, potentially imported from the Cote d’Ivoire where it was similarly manufactured with tools from Switzerland. And wait, there’s more – sugar, vanilla, milk solids, emulsifier, various milk derived products and all the machinery involved in their production, as well as the transportation of all these ingredients. That’s a lot of food miles.

Traditionally food miles measure the distance between the place where food is grown or made, and where it is eaten.

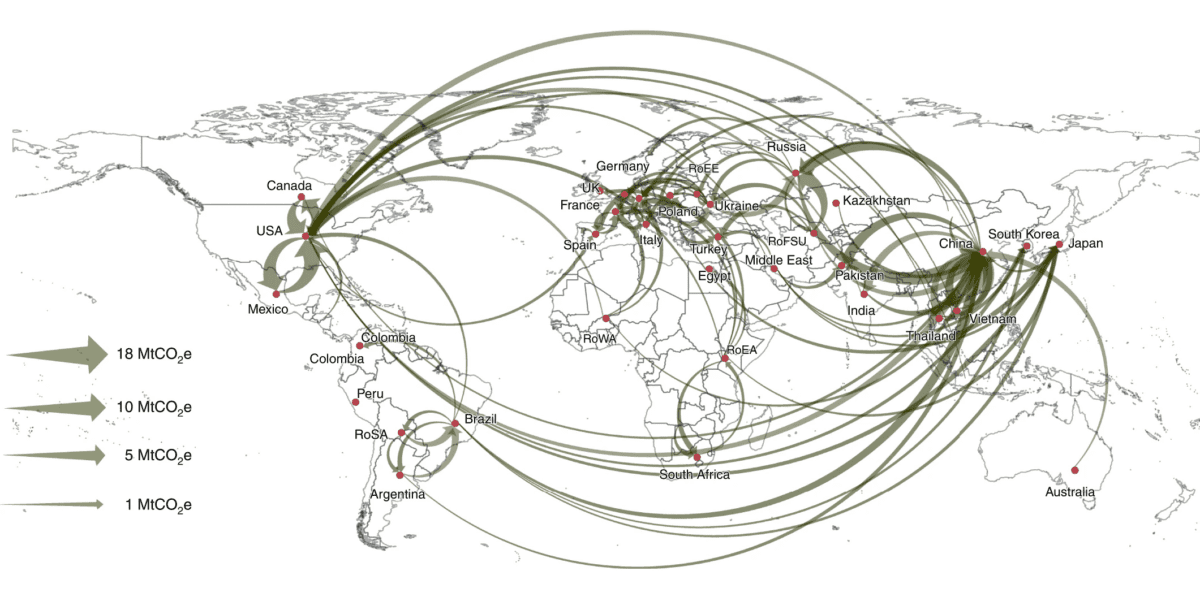

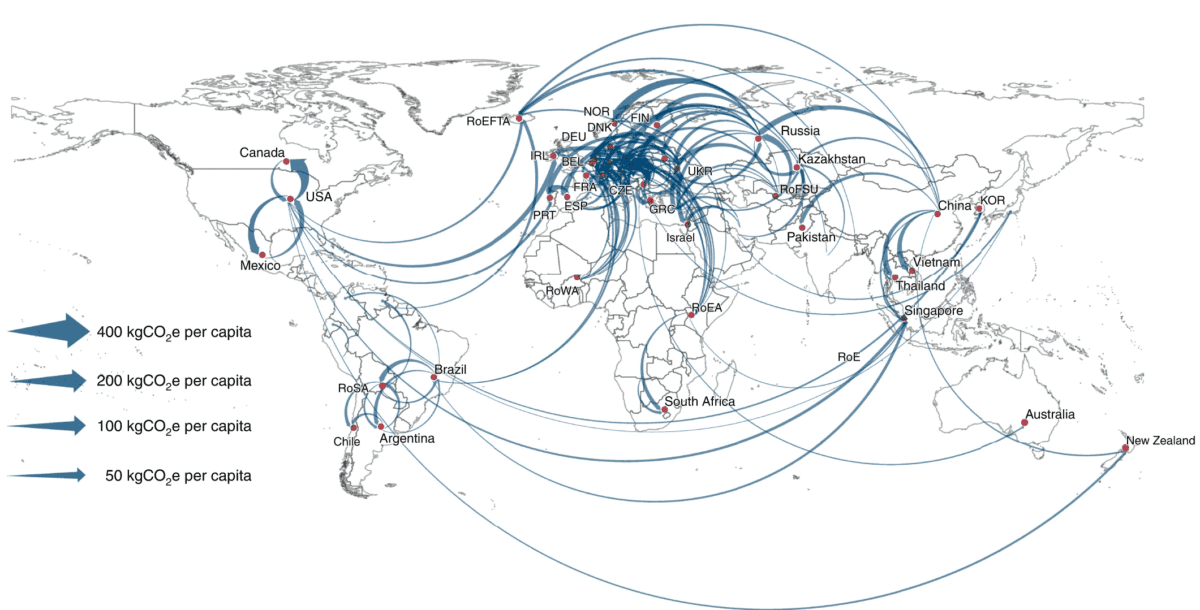

Our study has expanded this idea to account for the carbon footprint of food miles. By footprint we mean the entire supply chain for meeting our food consumption – so both food and non-food commodities, such as manufactured goods and services are part of this calculation.

We found that our food mile emissions are higher than previous estimates. Nearly 20% of all emissions in the production of food come from ‘food miles’ i.e., emissions associated with the transport of food and all upstream supply chains.

Supply chains – and their role in your carbon footprint

Until recently supply chains were probably not high on the radar of the general public. The massive disruptions caused by COVID-19 (when our orders did not turn up, or toilet paper became a prized good) and the carbon emissions of fossil fuels used in transport have certainly lifted the profile of supply chains as something of pressing concern to all of us.

Now reducing the use of fossil fuels in transport has become a significant policy goal for governments and organisations around the globe. Likewise unpacking these linkage effects in the supply chain for our daily foods is also important in the development of policies that will engage with the different actors along the supply chain stages to achieve a low-emission food system.

The miles in our food

We produced a production-layer-decomposition graph which shows how much emissions are from food and non-food commodities and in which supply chain layers.

Specifically, we breakdown the total footprint of food miles’ emissions into contributions from upstream production layers. This involves quantifying emissions at layer 1; emissions at layer 2: suppliers; emissions at layer 3: suppliers of suppliers and so on, to capture millions of supply chain networks.

Up to now most of the focus in reducing food system emissions has been on the high emissions linked to the production of animal derived foods (e.g. all those methane belching cows) rather than plants. And fair enough – there is a lot of evidence that animal production accounts for 57% of global greenhouse gas emissions from the production of food.

We were able to show that other food-miles matter. For example, the consumption of vegetables and fruits makes up more than a third of global food miles emissions. Moreover, we found the entire supply-chain environmental impact of transporting fruit and veggies to market could double the impact of growing the produce.

So – the footprint of food miles and their emissions – MATTER.

Would eating ‘local’ foods help?

To a point. Yes, we show that localising food supply in an international context leads to food-miles emissions reductions by around 10%. Just 10%, that does not seem like a significant saving right? That’s because eating locally harvested foods would involve substituting (relatively) low-emissions maritime shipping with high-emissions truck transport. But clearly it is not enough.

What’s to be done?

We need to expand the conversation to include the entire value chain – not only producers and consumers but also food processing, packaging, transport, retail and food services. This could include wholesalers, hospitality providers, investors, governments – we all need to be part of the solution.

The takeaway

It’s not just up to governments or business to help reduce emissions – we can all do our bit to reduce carbon emissions: shifting to a plant-based diet, eating local (see above), eating seasonal alternatives and using cleaner modes of transport.

Image: Jimmy Dean

Mengyu is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Integrated Sustainability Analysis group at the University of Sydney. Her research interests include lower carbon energy system modelling and electric vehicle-grid integration. She was part of the team that won the 2022 Eureka Prize for Excellence in Interdisciplinary Scientific Research.

Arunima is a Senior Lecturer in the Integrated Sustainability Analysis (ISA) Group at the University of Sydney. Her research is interdisciplinary, and focusses on the appraisal of social, economic and environmental impacts using input-output analysis. She was part of the team that won the 2022 Eureka Prize for Excellence in Interdisciplinary Scientific Research.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.