Harvest season is also peak time for conflict in rural societies

During their wars of conquest in Indonesia towards the end of the nineteenth century, the Dutch timed their scorched-earth campaign to coincide with the onset of the rice harvest season, not only to advance into dry or drained lands more easily, but also to seize food and maximise the damage to the local population.

At around the same time, when droughts of biblical proportions plagued the highlands of Ethiopia, food shortage turned provincial governors and their warriors into foraging bandits, while trade routes within Ethiopia and neighbouring countries fell victim to raids aimed at appropriating imported grain.

These anecdotes point to an inherent linkage between agriculture and conflict. In regions where agriculture holds a prominent place in the economy, a significant number of conflict incidents, especially of a communal type, can be attributed to it.

Agriculture: the source of income and the cause of conflict

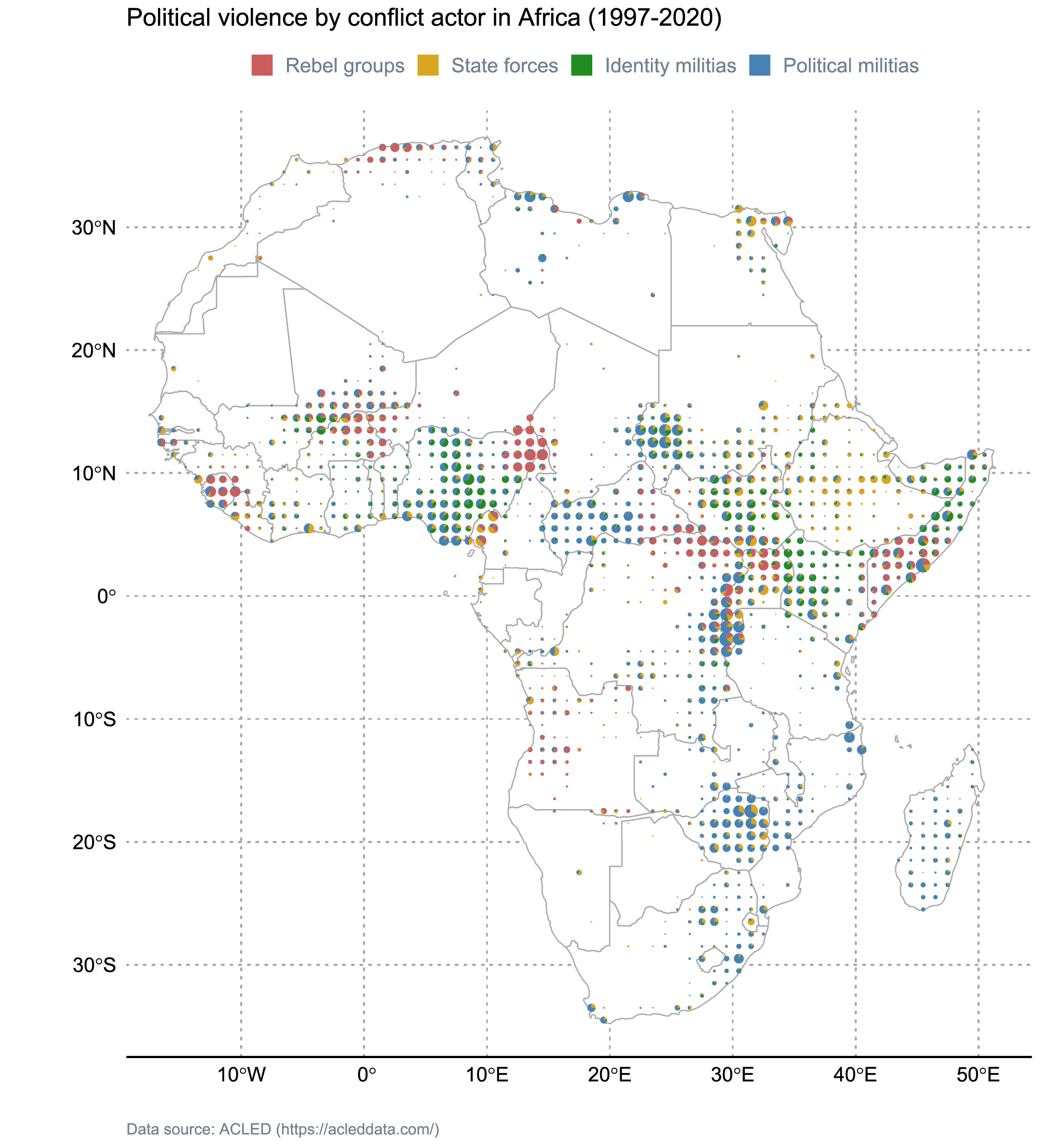

With my colleagues Justin Hastings and Kadir Atalay, I studied more than 55,000 violent incidents against civilians by paramilitary groups across Africa that occurred between 1997 and 2020. We sought to quantify the relationship between the harvest season and human conflict in predominantly rural societies.

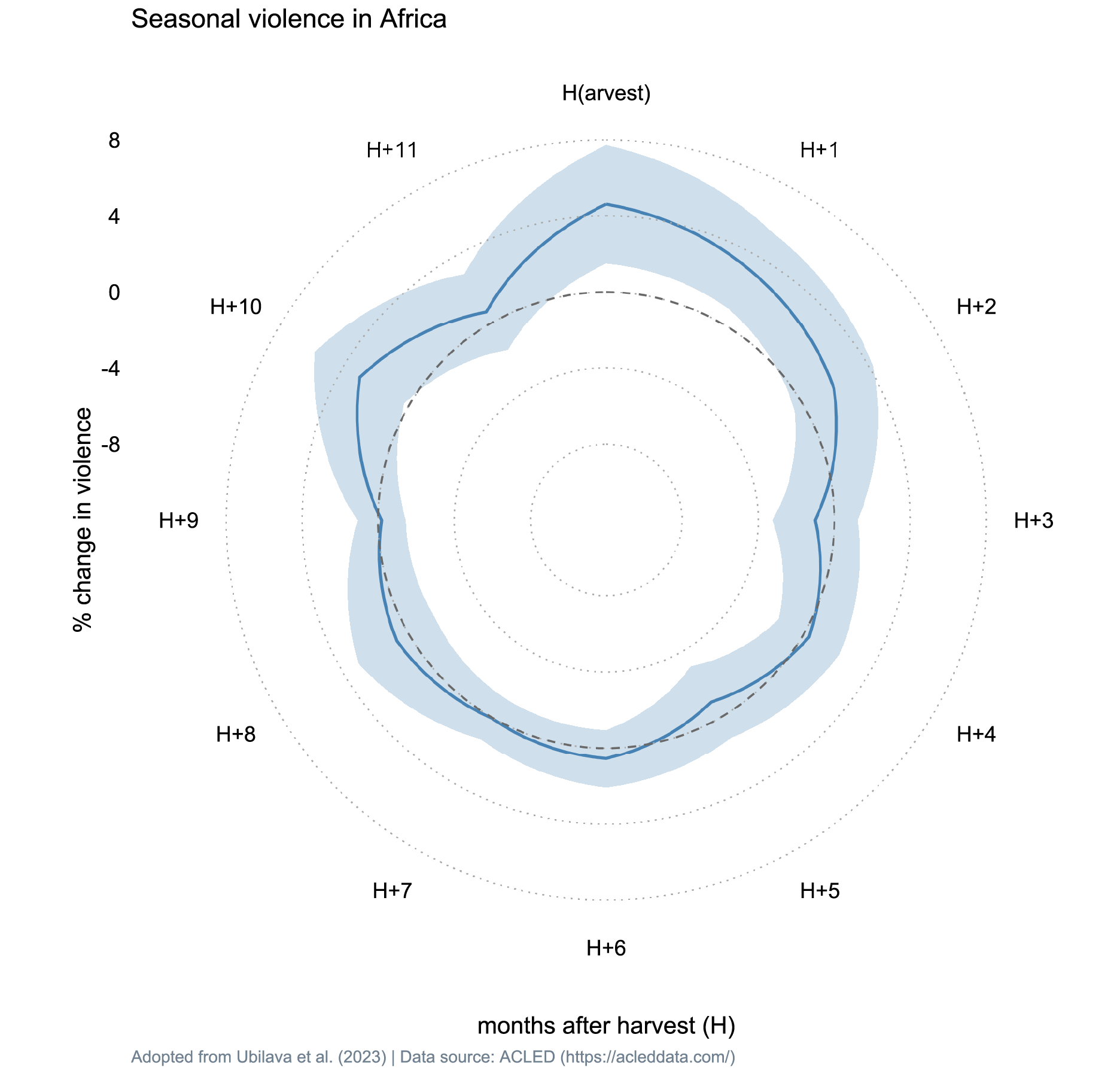

We observed a 10% rise in political violence against civilians in rural Africa immediately following the harvest season. This effect manifests in response to a one standard deviation year-on-year price growth of the cereal grain grown in a location, which alludes to rapacity as the key mechanism driving the conflict. That is, conflict is presumably associated with harvest time changes in the volume and the value of goods that local farmers harvest.

In a related study, Justin Hastings and I examined more than 70,000 incidents of civil conflict and social unrest across Southeast Asia during the 2010-2022 period. In this region too, we observed a 12% increase in the probability of violent attacks in rice-producing locations compared to the other parts of the region, during the harvest season relative to the rest of the year.

Harvest season means a spike in income…and violence

An important feature of agriculture, and the realised income from this sector, is its seasonality. Farmers make money largely when they harvest and then sell their crops. We found the seasonality of agricultural income translates into the seasonality of conflict: attacks on civilians intensify during the harvest season and dissipate as the crop year progresses.

It might seem counterintuitive that food abundance at harvest time amplifies—rather than mitigates—conflict. After all, throughout history, wars and rebellions have happened in the wake of natural disasters induced by droughts and famines. But in those instances, the forms of violence—especially looting and robberies—are perpetrated by less privileged groups of people targeting those with better access and capacity to store surplus food. Accused of stockpiling food, for example, missionaries operating in the region of current-day Tanzania became the target of hungry people amid the drought-induced food shortages toward the end of the 19th century.

In recent years, whether direct targets or a by-product of a larger military conflict, farmers across Africa and Southeast Asia have fallen victim to political violence. Records obtained from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) Project corroborate this. In August 2015, Boko Haram raided the village of Awonori (Nigeria), killed seven residents, and carted away food supplies and livestock. In July 2016, Perci beat a farmer and stole a bag of rice in Mbulula (Democratic Republic of Congo). In March 2017, gunmen shot and killed a farmer as he resisted an attempt to loot his sorghum on his way to market in Kwajieno County in Wau (South Sudan). In July 2019, Ahlu Sunna Waljama’a (ASWJ) attacked farmers harvesting rice, burned plantations, and stole food in Malinde (Mozambique).

Insights for improving peace in rural societies

These anecdotes, which are just a few of many thousands of data points in our analyses, point to the key channels that link agriculture with conflict. Facilitated by predation motives, violence can result from perpetrators trying to extract food for their own consumption or destroying food and resources as a way of inflicting harm on their opponents and opponents’ supporters. Whatever the cause, an opportune time for raids is when the intra-year availability of agricultural output or the related income has just materialised. That is when it becomes more beneficial for perpetrators to direct their resources toward either extracting or destroying the relatively more valuable agricultural products.

Knowing that political violence is likely to intensify at the time of harvest is an early warning system embedded in the croplands of these conflict-ridden regions. Because we know exactly where and when the main harvest season kicks in, we hope our study may serve as a guide for local governments and international organisations to make geographic and temporal adjustments to the scope and extent of their operations in their attempts to introduce and reinforce peace in the region.

Image: Polina Rytova

David Ubilava is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Sydney. His research interests are in commodity markets and price analysis.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.