Hans Hendrischke

China’s economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic

Absent any major setback, China is achieving the V shaped economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

China’s advantage in dealing with the pandemic are a nationally coordinated response supported by highly efficient social control and economic support at local level. But with the US-led economic and technological decoupling of Western economies from China, the Chinese post-COVID economic strategy includes an additional global dimension.

First, coming out of the pandemic, China has stopped GDP growth from further contracting below the 6.8 percent drop during the first quarter of 2020 and managed a successful turnaround of 3.2 percent GDP growth for the second quarter. China is on track to potentially achieve an annual growth rate of two to three percent, higher than the one percent growth predicted the IMF and the World Bank earlier in the year. This sets China apart from the negative annual growth expectations of all major economies. Some observers argue that China’s official growth rates are overstated, but domestic sales in cars and homes are recovering and China’s export in June 2020 was up half a percent against a drop in global trade of 16 percent, suggesting that China’s economy is making up for lost growth. Nicholas Lardy of the Peterson Institute for International Economics who is the leading authority on Chinese economic statistics, estimates the Chinese economy in 2021 could be 10 percent bigger than it was in 2019 whereas the US, Canada, Japan and the major European economies will be shrinking.

Second, China has used all macroeconomic tools at its disposal to achieve this recovery, including stimulus funding, interest rate reductions, tax relief and support for the large state-owned enterprises sector. But in addition to these central government policies, China has local demographic and governance advantages that are hard to imitate.

Affluent middle class will pull Chinese economy out of COVID blues

China owes its rapid economic snap-back to the domestic purchasing power of its middle classes – the 500 to 700 million strong middle income group (SCMP 24/5/2020). This middle income group sustains demand for domestic goods and services as well as imports from around the world in addition to demand for social infrastructure in healthcare, social welfare, aged care, education and new technologies. China’s post- COVID-19 recovery policies have targeted this mainly urban based population. The digital connectedness and mobile consumption habits of this large population have made it possible, for example, to issue 19 billion RMB (2.7 billion USD) worth of consumption coupons and stimulate online – purchases through digital platforms that can target specific localities and industries.

Deep regional stimulation keeps local economies powered

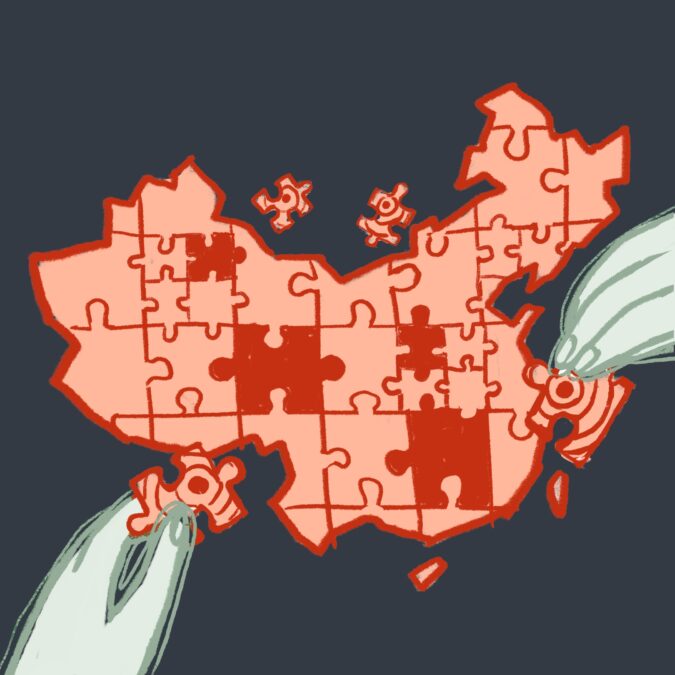

The same digital connectedness has made it possible for local governments at the level of the approximately three thousand counties and below to target private sector enterprises and SMEs with subsidies and stimulus measures. These local enterprises are the backbone of employment and job creation. China now reaps the benefits of a decade of reforms to its public finance and local taxation system which was introduced by Xi Jinping leadership over nearly a decade since 2013. Secure funding of the decentralised governance structure enables local governments to direct stimulus funding to local consumers, local enterprises and local infrastructure. Local economic policies of this granularity are hard to achieve in economies with more regionally focused or centralised governance structures.

Third, this dual economic governance of a centrally controlled economy that includes the large central state-owned enterprise sector and largely autonomous local economies relying on local enterprises have produced the resilience that has helped the Chinese economy to recover from the pandemic. Contrast this with the supply side stimulus funding in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, when the central government invested in physical infrastructure and local governments. In the richest parts of China, counties and townships were building local government compounds larger than national government compounds in some Western capitals, only for the purpose of absorbing unplanned for stimulus funding. China’s economic crisis management in 2020 is more targeted and locally specific. As a consequence China, through economic growth, will be able to support other economies on their way out of recession through foreign trade and investment.

Foreign trade and investment are China’s exposed economic flank

Fourth, foreign trade and investment, however, are potentially the weakest points in China’s economic resilience going forward because of the precarious geo-strategic situation China finds itself in. The US-led economic and technological disengagement from China could weaken China’s global competitiveness in ways difficult to foresee. China’s promotion of free trade and the Belt and Road Initiative now look like defensive moves to make up for the potential loss of markets in developed countries and access to advanced global technologies in the longer run if a global technological divide were to emerge. This is by no means certain. Multinational corporations are not intent on withdrawing from the Chinese market. The most recent survey of the Beijing US Chamber of Commerce shows that 83 percent of US firms operating in China intend to stay.

Chinese investment into Australia likely to continue to plummet

Fifth, Australia is in a peculiar situation in regards to China. Dealing with China as its major trading partner is highly rewarding. Unlike most other countries, Australia gains a huge trade surplus from its goods and services trade with China. In 2018, Australia’s trade surplus with China amounted to A$58.26 billion, accounting for more than 250 percent of its total trade surplus (A$23.23 billion) and allowing Australia to run a trade deficit with other major trading partners including the US, the U.K. and ASEAN. Economically, Chinese demand for Australian exports is stable due to the lack of alternative supplies for the major resources exports of iron ore and coal and solid consumer demand for high quality produce and services by middle class consumers. Australian economic disengagement from China is therefore more likely to happen for geo-strategic than for economic reasons. Australian reliance on the Chinese market will decrease as China is also looking for alternative foreign or domestic suppliers of resources and agricultural produce. This is reflected in the sharp decline in Chinese direct investment in Australia which dropped by over sixty percent in 2019.

Shifting supply chains will bring Chinese production closer to foreign consumers

Sixth, China’s post-pandemic economy is affected by the restructuring of global supply chains which has been going on for several years, but is being accelerated by the pandemic. The countries that will benefit from the break-up of China-focused supply chain will mainly be neighbouring countries in East and South East Asia. Decentralisation of production is expected to happen in two ways. One is by foreign investors in China moving part of their capacities to neighbouring countries in the so-called China plus one solution. The other way for investment flowing out of China is by Chinese companies outsourcing part of their operations to other countries. This has been happening for some time, for example by Chinese companies outsourcing their accounting or HRM administration to Malaysia or production facilities to Vietnam or Cambodia. An emerging trend is for Chinese manufacturers to move production closer to consumers in developed as well as developing countries. This trend will be accelerated once 5G technology and digital manufacturing become more widely available.

Seventh, China economic planning is adjusting to these changes. Economic planning for 2020 was adjusted in May 2020 during the delayed sessions of the Chinese legislature. Domestically, the ‘Major tasks for economic and social development in 2020’ focus on containment of the pandemic, social stability and economic recovery. More specific policies aim at supporting the private SME sector and technological upgrades of the digital economy.

China will continue to quarantine foreign investment

China’s response to the international economic challenges is more guarded. Progress in improving working conditions is slow and piece-meal with small steps in specific industries, such as increased foreign ownership in the finance sector and continued gradual opening up of previously closed industries. The opening-up agenda is still characterised by the ‘pilot zone’ approach that has worked for domestic economic reforms, but is frustrating for foreign investors when a breakthrough in market access to China turns out to be a pilot zone in the tropical island of Hainan which is renowned for its tourism and real estate business.

The 14th Five Year Plan from 2021 to 2025 which will is likely to be announced stepwise from March 2021 is focused on the domestic economy with raising living standards, poverty reduction, health, environment and technological progress the main concerns, but little indication so far of any major change in international economic policies. What is notable is the emphasis on China having to be prepared for all eventualities.

Hans Hendrischke is Professor of Chinese Business and Management at the University of Sydney Business School. He leads the School’s Australia China Business Network and chairs the Business and Economics Cluster of the University’s China Studies Centre.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.