Martin Tomitsch, Madeleine van Venetie and Melinda Gaughwin

For the sake of the planet we need to rethink human-centred design

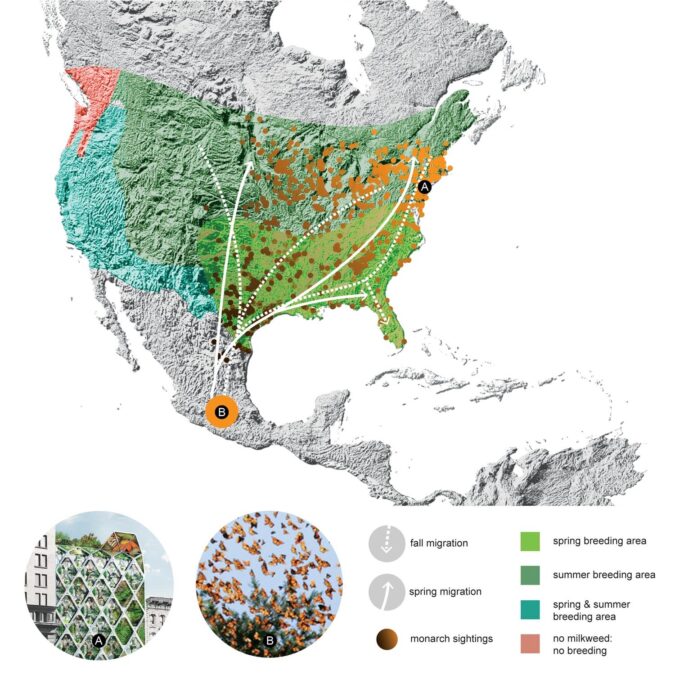

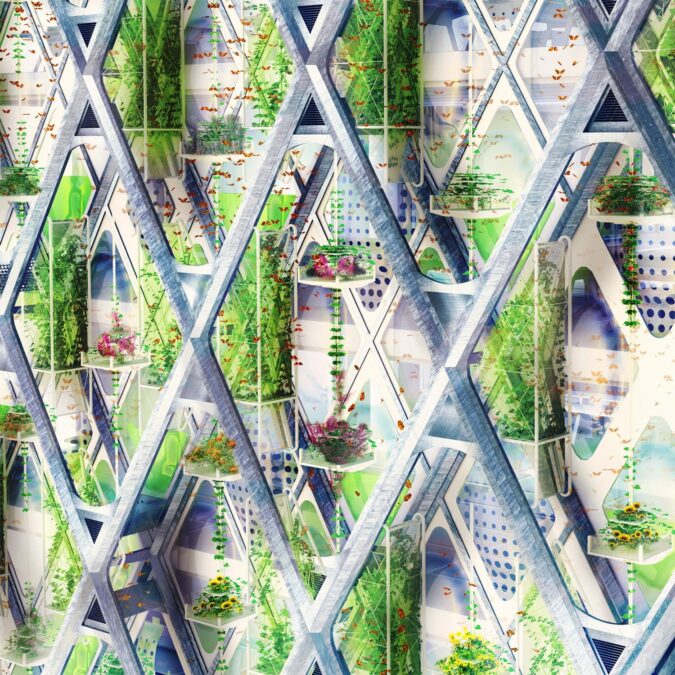

Considering the plight of an endangered butterfly is not a conventional approach when designing the façade of a high-rise building in New York City. But when architecture firm Terreform ONE proposed a double skin façade for a commercial building in the Nolita District, a key consideration was building a sanctuary for the monarch butterfly.

Its brilliant orange-red coloured wings transport this noble butterfly from North America to Central Mexico, but disappearing green spaces where it can lay its eggs enroute is threatening the existence of the monarch butterfly.

The still-to-be-completed ‘Monarch Sanctuary’ embodies a life-centred design approach. Milkweed plantings, nectar flowers, and semi-enclosed spaces offer habitat and breeding ground for monarchs. The building’s human occupants will benefit from a restorative green outlook that will boost productivity and mental health. To amplify its impact and raise awareness about the looming extinction of local species, a series of media screens will display live camera feeds of nesting caterpillars and butterflies.

Life-centred design – an emerging design framework – obliterates the idea that humans are at the centre of everything. It expands human-centred design methods to consider all creatures and the planet.

Over the last 50 years human-centred design was embraced by companies seeking to develop better experiences and to drive innovation. However, there is mounting evidence that placing the consumer at the centre of the design process is actually harming human wellbeing, as its narrow focus is damaging the global systems essential to our prosperity.

Human-centred design: Key milestones

- 1955: Henry Dreyfuss’s “designing for people” puts importance on the ergonomics of the human physical form in design

- 1970s: The rise of cognitive science and personal computing helps the human-computer interaction profession to develop

- 1988: Donald Norman publishes “The psychology [design] of everyday things” which helps designers to understand the role of cognition in design

- 1991: David Kelley founds the design consultancy IDEO and, drawing on work from Stanford University, adapts human-centred design as a business strategy

- 1995: Donald Norman coins the term “user experience” while working at Apple

The rise and rise of human-centred design

Placing people at the centre of the design process emerged in response to the pace of technological development toward the end of the 20th century. Human-centred design is what set an Apple apart from an IBM computer in the early days of desktop computing. It’s what made IDEO one of the most recognised design innovation agencies in the world. It’s key to the success of upstart tech companies like Uber and AirBnB that disrupted centuries-old markets with their human-centred digital platforms.

Human-centred design has enabled technological progress and innovation through unearthing new applications – discovering things that people want. But what started as a well-intended approach to make it easier for people to use interactive products, is now tightly woven into the world’s commercial fabric.

In other words, human-centred design is good for business. At first sight it seems great for the consumer too. After all, it delivers the things we want. But those things come with unintended consequences.

Infinite regret

In 2019, Aza Raskin, the creator of infinite scroll, publicly expressed his regret about the addictive behaviour resulting from his invention. Reflecting on his creation, Raskin wrote on Twitter that “optimizing something for ease-of-use does not mean best for the user or humanity”. Sadly, lessons about unintended consequences are largely ignored in practice. Organisations and tech startups too often continue placing shareholder value and short-term gains above all else.

One such startup is Juul, a business selling nicotine vaping products. Juul’s co-founders studied human-centred design thinking at Stanford University. Their findings led them to creating a vaporiser that eliminates shame and other negative elements associated with smoking. Their products also propagate smoking in young adults. Like many other tech businesses, Juul would have benefited from a more holistic perspective. Failing to see the bigger picture also cost Juul a hefty fine.

The current neoliberal economic system gives little reward to those addressing systemic problems, instead emphasising growth to the exclusion of all other factors. As Annie Leonard, founder of the community movement “Story of Stuff”, argues, developed countries are playing a game where the goal is “more” not “better”.

From addictive scrolling to popularising unhealthy lifestyles, human-centred design has the power to create things that people want. But what people want is not necessarily good for their mental and physical health. Neither is it good for the health of the planet and for future generations, who will have to pay for the damage caused by the “growth above all else” mindset.

It’s time to recalibrate the contribution of human-centred design beyond consumption and towards sustainment. This requires a paradigm shift, one that decentres the human.

A new model for responsible innovation

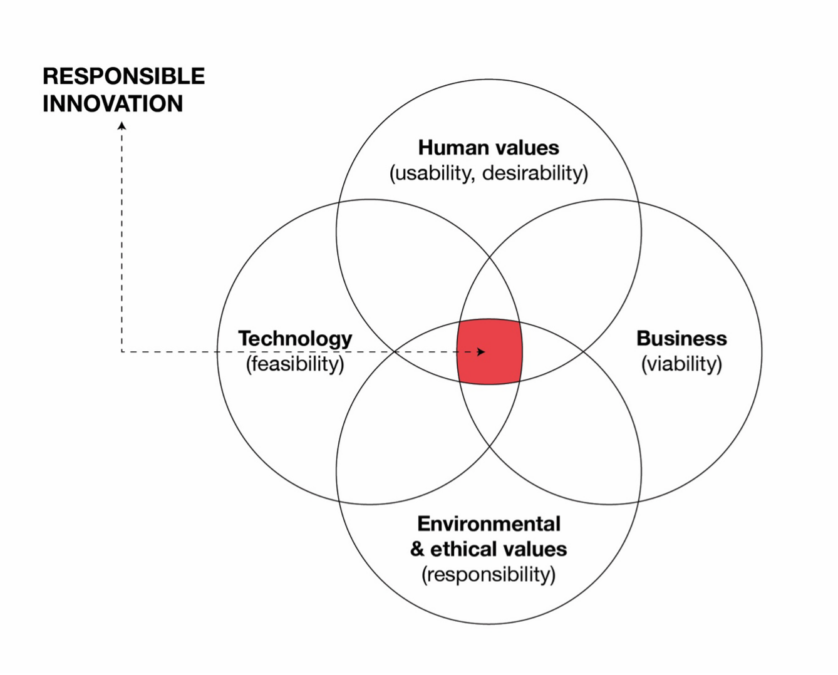

For the past decade, the tech industry has largely followed a model for human-centred innovation popularised by Palo Alto based design company IDEO. Depicted as three intersecting lenses the circles represent the ideal balance between desirability, viability and feasibility.

Life-centred design extends this model by adding a responsibility perspective. This includes carefully considering the environmental (i.e., the impact on the planet and ecosystems) and ethical (i.e., the unintended consequences for people and communities) values of design proposals alongside technology, business and human concerns.

Designers are ideally placed to take on custodianship of the responsibility perspective. As custodians, their role is to ensure the relevant concerns are represented during the design process. This includes advocating for non-human stakeholders and ecosystems that would otherwise not have a voice in the design process.

New opportunities

COVID-19 presented nations with an opportunity to implement a systemic shift to more sustainable economies attendant to both the needs of people and those of the planet. This echoes calls by the World Economic Forum for companies to act “as a steward of the environmental and material universe for future generations”.

Organisations have a unique opportunity to be leaders of positive change. This also offers economic benefits for businesses. Consumer expectations are also changing due to a growing awareness of climate change and stakeholders are demanding accountability to address negative impacts.

Life-centred design offers organisations an approach to systematically go beyond mitigation and demonstrate positive environmental and societal benefits.

Image: Alex Guillaume

Martin Tomitsch is a Professor at the University of Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning. Through his work as design researcher and educator, he advocates for the power of design to imagine speculative futures and drive positive change within organisations.

Madeleine van Venetie is an interaction designer with more than 10 years of experience in UX design for pervasive technologies and digitally-enhanced environments. She is driven by critically improving interaction design practice, and teaching her students at the University of Sydney to be great designers.

Melinda Gaughwin is an Associate Lecturer in the Design Lab, located in the School of Architecture, Design and Planning at the University of Sydney. Her research investigates the ways in which design politically shapes people's material and immaterial everyday lives, and how critiques of design can uncover this shaping.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.