Cameron Murray and Josh Ryan-Collins

When houses earn more than jobs: how we lost control of Australian house prices and how to get it back

Real home prices across Australia have climbed 150% since 2000, while real wages have climbed by less than a third.

Sydney and Melbourne rank among the most expensive cities in the world. Australia-wide, home ownership levels have fallen from 70% to 65% in the last 20 years and home equity levels have fallen from 80% to 75%. Younger workers have been completely priced out of the major cities.

Among those who can afford homes, the increase in household debt to income ratios is weighing on consumption and increasing financial fragility.

We are often told the problem lies in supply — we don’t have enough homes in the places people want them. And while it’s true a reduction in the supply of housing relative to the population will reduce housing per person and increase housing rents, what we are seeing is something different — a growing divergence between rents and the price of housing as a financial asset that’s increasing much more quickly.

Australia has become something of a world leader in demand-driven home price inflation. Australians have been increasingly buying housing for the purpose of securing financial returns — both capital gains and rental income, in a process often described as the financialisation of housing, but one that we think can be more accurately thought of as “rentierization”.

How it happened

In a working paper published this morning by the University of Sydney and the University College London Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, we argue “rentierization” best describes the increasing use of housing to extract land rents, in the form of capital gains on property and rents from tenants — a process in which Australia is well advanced.

Despite multiple major boom and bust cycles, including Victoria’s 1880s land boom and the 1890s recession that followed, land values and home prices were relatively low compared to the total value of economic activity right up the 1960s.

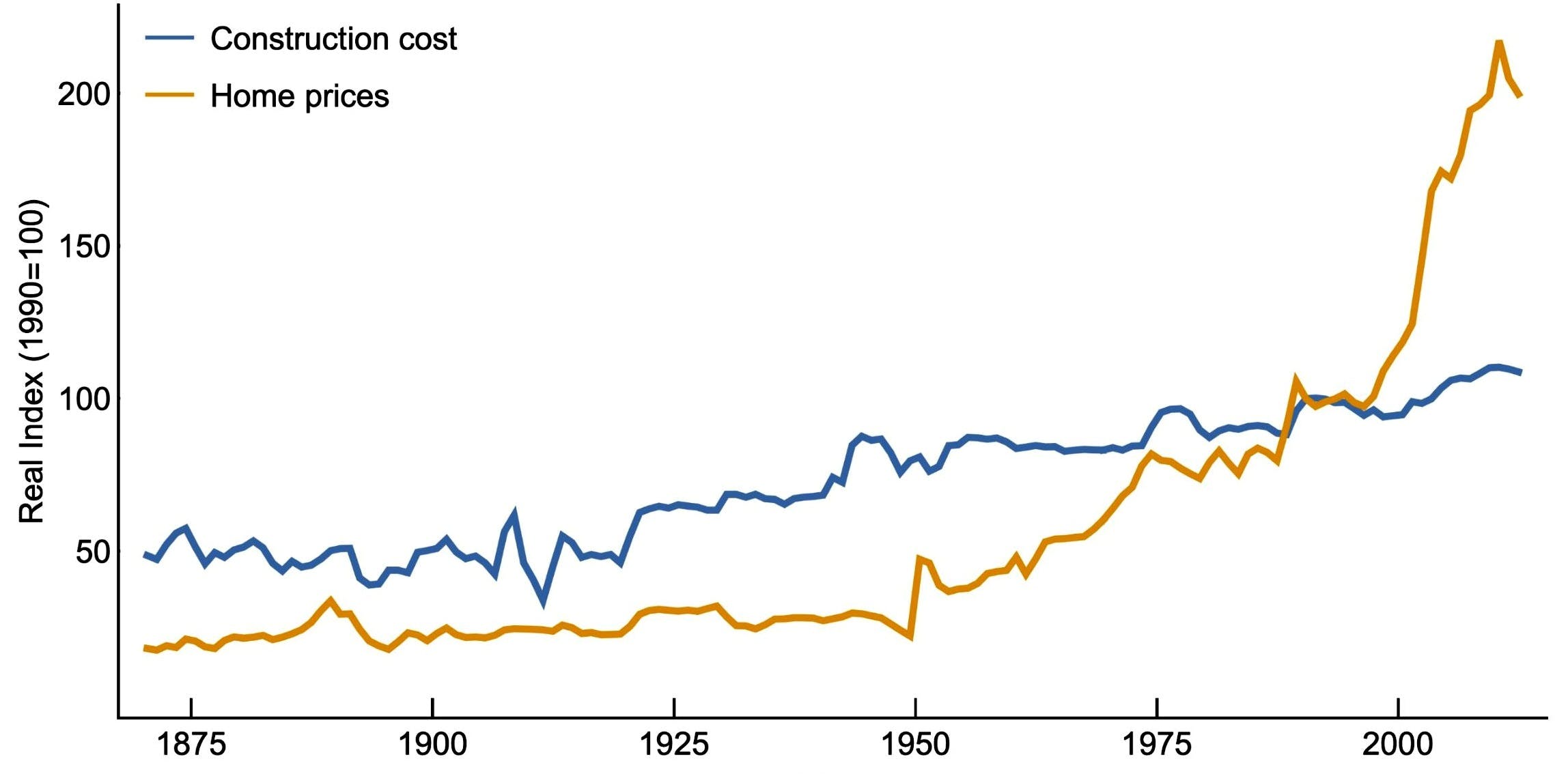

Long-term Australian real price index for housing and construction prices

In contrast, we show, real Australian home prices have soared 215% since 1980 and have shown few signs of reversion to long-term trends, despite brief corrections in 2009-10 and 2017-2019.

The graph shows the rise in home prices has been driven by rising land values rather than construction costs, which have grown at a rate closer to general price inflation.

It’s tempting to ascribe the takeoff in home prices to low interest rates. Low rates enable households to take out larger mortgages relative to their incomes.

But rates were also low in the 1960s (close to rates in the 2010s, when home prices were soaring) and didn’t much push up prices then.

More from the house than the wage

Low rates appear to be a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for soaring prices. Among the other things that seem to be needed are increased access to finance, declining public involvement in housing, and tax breaks that reflect the political power of owners.

The return to land in the form of capital growth has climbed from around 3.5% of gross domestic product before 1960 to 16.7% of GDP since 2000.

It has become so high as to rival and at times dominate wages as a source of household income.

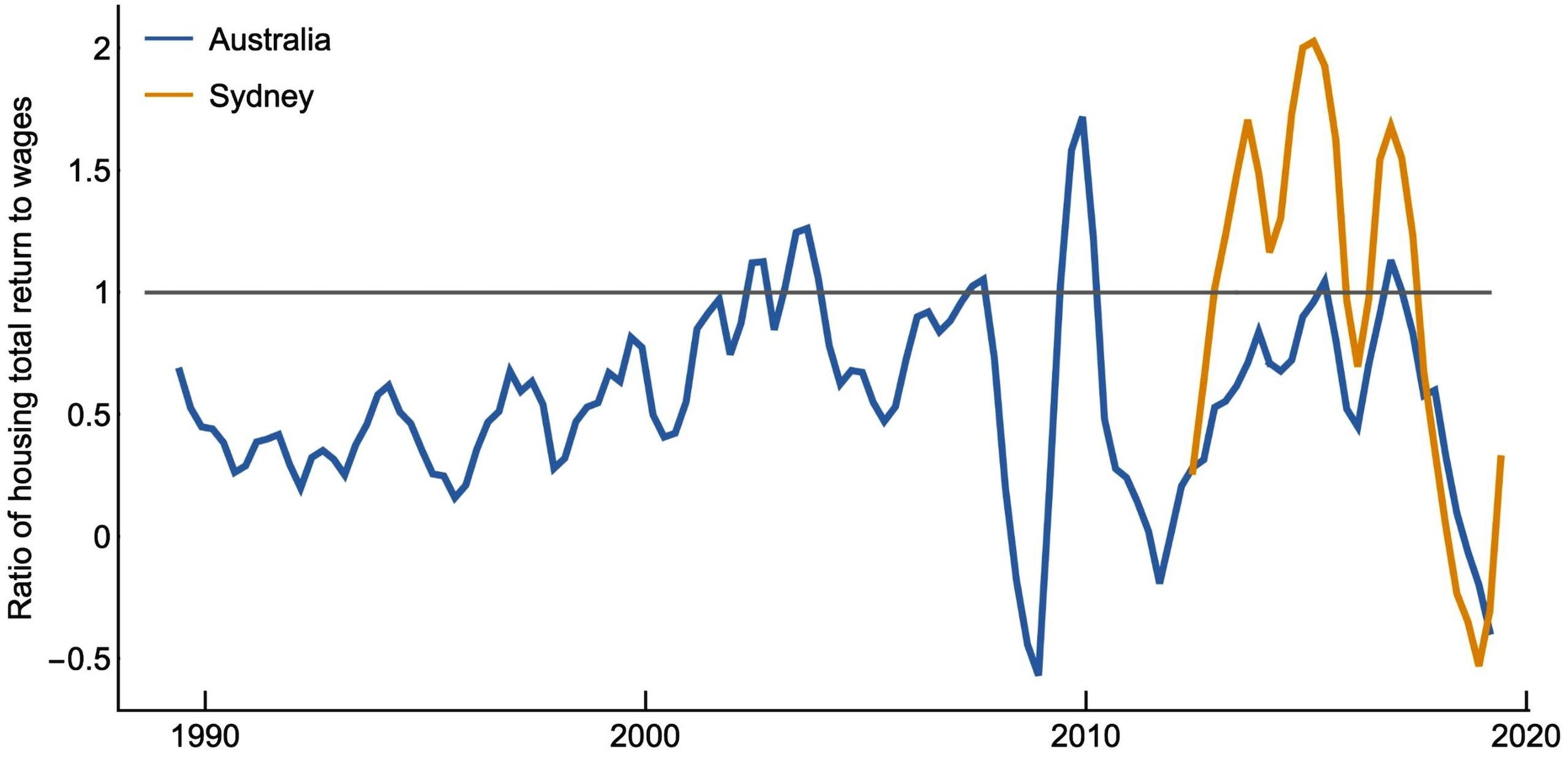

The graph below compares the annual return to a typical home over a year with the annual return to labour in the form of a wage, both nationally and for Sydney (where only recent data is available).

When the measure is greater than one it implies that the average home had a greater return, made up of rent and capital gains, than the average worker.

Total return from housing compared to wages

In 16 of the 29 quarters leading up to June 2019, the median Sydney home earned more than the median full-time worker earned from wages.

In Australia, housing is overwhelmingly privately owned. For a brief period in the 1950 and 1960s, public housing was created on a significant scale, but a huge privatisation program soon followed and today it represents just a few percent of new supply.

Into this environment was thrown the removal of controls on lending from the 1980s, enabling banks to expand property-related lending.

More credit flowing in to a finite supply of land generates a feedback cycle as rising prices and collateral values stimulates more lending and higher prices.

In Australia, mortgage lending grew from just under 20% of GDP in 1990 to over 80% today. By way of comparison, business lending climbed 35% to 40%.

The vast majority of mortgage lending is for the purchase of existing, rather than new, homes.

Investors push up prices for everyone

The investor share of new mortgage lending has grown from 10% in the early 1990s to 40%. It has given owner occupiers and first home buyers price competition they didn’t previously have to face.

Australia’s unusually generous tax concessions for investors helped. They are granted discounts on capital gains tax, while being able to deduct the full costs of operating their properties, (including interest costs) against income from any source.

Where the deductions exceed rental income, the process is known as negative gearing.

A lot will need to change in order to shift things. Mortgage credit will need stronger regulation. It may be time to revisit the credit controls used in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s, which directed investment into new rather than existing housing and helped increase home ownership.

The case for a central housing bank

Taxes should focus on land rents, in the form of increasing residential property values or windfalls from changing land use. Taxing away future rents would dent speculation.

Broadening annual land value taxes to primary residences as well as investors housing would be part of the change, introduced at a low initial rate and with options for delayed payment or borrowing against future sales for those on low incomes.

Tax advantages extended housing investors, such as negative gearing and discounted capital gains taxes, should be scrapped.

And there’s a case to reintroduce direct government involvement. A central housing bank could use its ability to supply and sell new housing to set a “home price corridor” to ensure home prices did not rise rapidly and dampen potential falls in prices.

It could also be used to provide a variety of alternative stable tenures for households, such as different kinds of renting, public housing and selling dwellings to social housing providers at discounted prices.

Challenging vested interests will be hard, but the current downturn offers hope.

As rates of home ownership fall, renters struggle to make ends meet and central banks run out of leverage to stimulate the economy with interest rates already at rock-bottom, reforms that previously appeared politically impossible might gain traction.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Maximillian Conacher

Cameron is a Research Fellow - Henry Halloran Trust at the University of Sydney. He specialises in specialising in property and urban development, environmental economics, rent-seeking and corruption.

Josh is the Head of Finance and Macroeconomics at the Institute of Innovation and Public Purpose, UCL. He is an economist an author with interests in the economics of land and housing, money and banking, sustainable finance and economic rent.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.