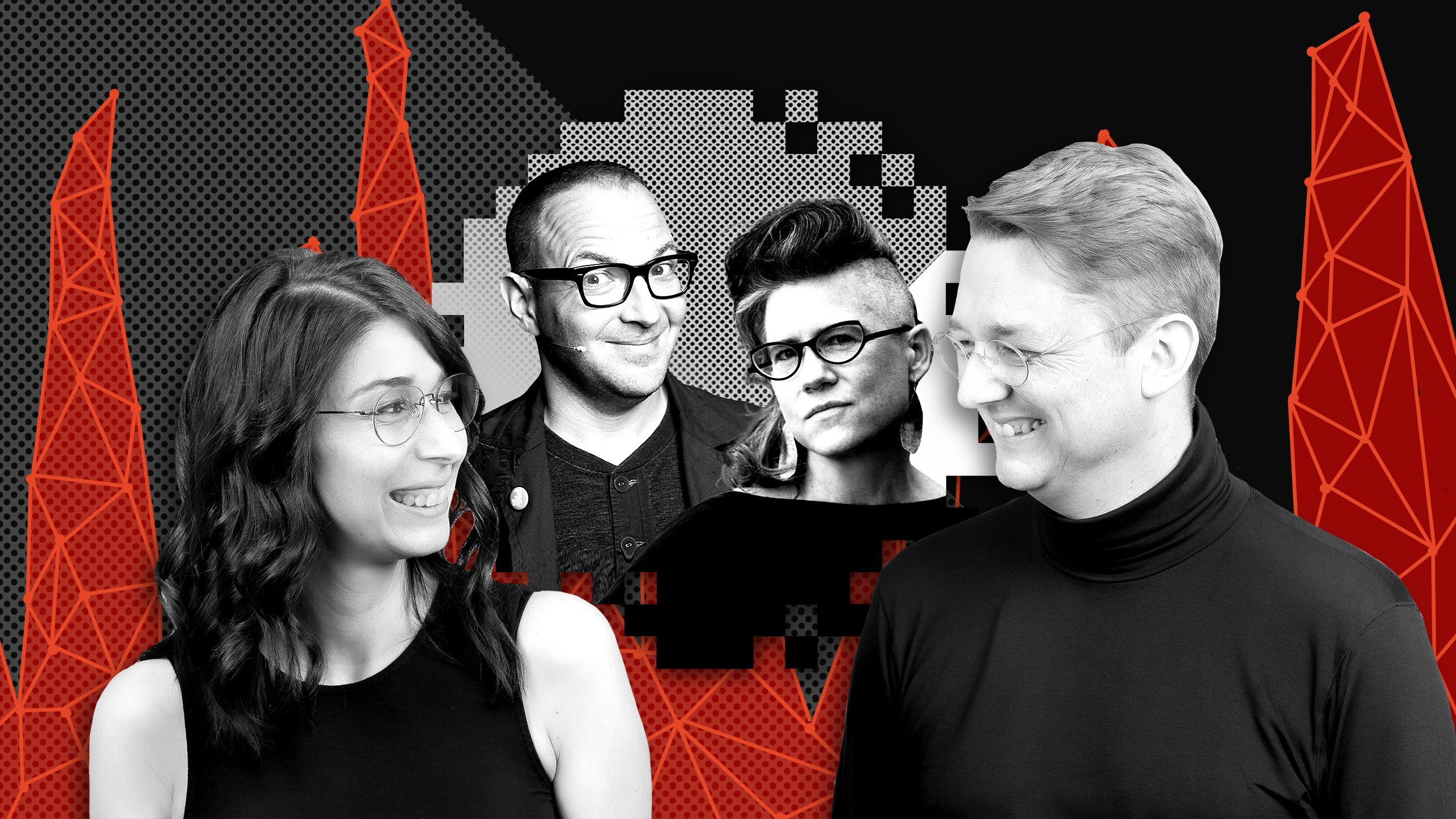

Sandra Peter, Kai Riemer, Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow

Platform capitalism with Cory Doctorow and Rebecca Giblin

This week: we interview Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow, authors of Chokepoint Capitalism, about how platforms capture value in creative markets.

Sandra Peter (Sydney Business Insights) and Kai Riemer (Digital Futures Research Group) meet once a week to put their own spin on news that is impacting the future of business in The Future, This Week.

Our special guests this week

Other stories we bring up

Our previous episodes of The Future, This Week discussing #BreakUpBigTech and more #BreakUpBigTech

Our previous discussions of platform monopolies and antitrust, missing platform competition, the societal responsibilities of social media platforms, and the fragmented internet

Our episode of The Unlearn Project on unlearning the music industry

Rebecca and Cory’s book, Chokepoint Capitalism

Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia

The Mister Gotcha comic by Matt Bors

We need your help to vote for our session at SXSW Sydney!

In AI fluency: what’s coming for my job?, award-winning STEM journalist, Rae Johnston, will be joined by Sandra Peter and Kai Riemer from the University of Sydney Business School and Kellie Nuttall from Deloitte to discuss the state of AI and the future of work.

We’ve all seen how the conversation around artificial intelligence has changed since the launch of ChatGPT, but how should businesses, organisations, and the people who work for them, prepare? It involves knowing how AI works, what it can do, and what that means for the future: being AI fluent.

Follow the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts. You can follow Sydney Business Insights on Flipboard, LinkedIn, Twitter and WeChat to keep updated with our latest insights.

Send us your news ideas to sbi@sydney.edu.au.

Music by Cinephonix.

Dr Sandra Peter is the Director of Sydney Executive Plus and Associate Professor at the University of Sydney Business School. Her research and practice focuses on engaging with the future in productive ways, and the impact of emerging technologies on business and society.

Kai Riemer is Professor of Information Technology and Organisation, and Director of Sydney Executive Plus at the University of Sydney Business School. Kai's research interest is in Disruptive Technologies, Enterprise Social Media, Virtual Work, Collaborative Technologies and the Philosophy of Technology.

Rebecca is an ARC Future Fellow and Professor at Melbourne Law School, and the Director of the Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia. Her work sits at the intersection of law and culture, focusing on creators’ rights, access to knowledge and culture, technology regulation and copyright.

Cory is a science fiction author, activist and journalist. He is the author of books including Chokepoint Capitalism, Radicalized and Walkaway.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.

Transcript

Disclaimer We'd like to advise that the following program may contain real news, occasional philosophy, and ideas that may offend some listeners.

Intro From The University of Sydney Business School, this is Sydney Business Insights, an initiative that explores the future of business. And you're listening to The Future, This Week where Sandra Peter and Kai Riemer sit down every week to rethink trends in technology and business.

Sandra Let's talk a bit about platforms.

Kai Digital platforms have become part of our everyday lives, we get our music from them, we get our books from them, we use them to search. A lot of the things that we do revolve around the use of big tech, big platforms.

Sandra You would have used either Apple or Google to access anything mobile, you probably would have gone to YouTube to watch some videos, you use Spotify to listen to some music, Amazon to get your books.

Kai Audible to get your audio books. In many of these industries. There's now just one, or very few, platforms that dominate distribution of this kind of digital content.

Sandra And a few times on this podcast we raised issues around competition, around monopolies, antitrust legislation. And we've seen over the last few years, repeated discussions around either breaking up big tech or rethinking what we mean by antitrust legislation, because up until now, the traditional tests we had for undue market power...

Kai The common wisdom.

Sandra The common wisdom that, you know, it's bad for consumers, prices will go up, didn't quite work when we thought about platforms like Amazon.

Kai Yeah, in the digital space, things work differently, prices are actually quite low. Choice is there, the service is actually quite convenient for consumers. You get access to all this content, books, music, videos at the you know, press of a button.

Sandra At a very good price, and in many cases for free even.

Kai But that's not the whole story, right? We've discussed previously how these platforms can have problems at the other end of the business model. The fact that they start competing with their own suppliers, or they involve suppliers in hyper-competition and move into a position where they can extract value from those suppliers who now have no other way to reach customers, than through these platforms.

Sandra And when we say suppliers, most people think you know, the people who make backpacks or...

Kai Sneakers, clothing...

Sandra Hand sanitiser...

Kai Toilet paper.

Sandra But when it comes to digital content, we've always seen these platforms as something that enables creativity that enables, you know, little authors to publish their books or to make their songs known, gives them access to a huge market without having to jump through all the hoops to make their work available to broad audiences.

Kai And they're certainly told this story, so there's a positive aura around this kind of disruption. The way in which Audible gives us access to all these books, and Spotify gives us access to all the music in the world. But turns out...

Sandra Turns out that the position into which companies have manoeuvred themselves allows them to use their position so that creators, artists, authors receive a smaller and smaller share of the price of their work.

Kai On our recent trip to South by Southwest in Austin, we got to sit down with Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow, who together have written a book Chokepoint Capitalism: how big tech and big content capture creative labour markets and how we'll win them back. Rebecca and Cory have unpacked this phenomenon in detail, and they describe platforms as these chokepoints, as these hourglasses where you have lots of consumers on one side, lots of artists and creators on the other side, and sometimes only one platform in the middle, who creates this chokepoint to extract value.

Sandra So we sat down with Rebecca and Cory to try to unpack not only how this happens, which is relevant not only for artists, but for a variety of other suppliers, but more importantly also what can we do about it?

Kai How can we change the narrative and the understanding in the general public so that people become aware of what's actually happened because it's fairly well hidden in those business models.

Sandra So let's hear what they had to say.

Rebecca Giblin I'm Rebecca Giblin. I'm a law professor at Melbourne Law School and the Director, Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia. And I investigate questions around the intersection of law and culture.

Cory Doctorow I'm Cory Doctorow, I'm an activist and journalist, science fiction novelist, author of more than 20 books, most recently with Rebecca, Chokepoint Capitalism.

Kai Why don't we start by you telling us about your book Chokepoint Capitalism, what's the premise of the book? What is the observation?

Cory Doctorow Sure, so Chokepoint Capitalism describes a certain kind of market concentration that we think is distinct to a 21st century digitally enabled kind of platform economy. And under that circumstance, you have all of the customers for creative work being gathered into some kind of silo. They're locked in, either through technological choices or economic choices. Sometimes it's through the denuding of the competitive landscapes, there's nowhere else to buy things as a result of predatory pricing that exterminates other market participants. And once the audience is locked in, the creators can be locked into another silo, because they have to reach that audience. And then there's a chokepoint between them, a kind of hourglass shape. And at that chokepoint, you have these intermediaries, who rather than acting as people who help and facilitate audiences and creators connecting with one another, become kind of value extractors. Who not only get the final say, and what kind of work gets made and disseminated, but also end up taking the lion's share of the value.

Rebecca Giblin And it's not meant to be this way, you know, these lock ins that we demonstrate in the book, and we talk about in other different spheres other than creative labour markets as well. All of those market advantages were supposed to be temporary. And that used to be how things worked. But over the last 40 years, we've seen a systematic and deliberate elimination of competition. And this is the orthodoxy now taught in most business schools. Peter Thiel comes out and says, "competition is for losers". Warren Buffett talks about how he only wants to buy businesses that feature wide, sustainable moats. It's all about not making the things or providing the services that people need, but positioning yourself between the people who make and do and the people who need, and then using that power to mediate access to lock everybody in and use that power to extract more than your fair share.

Kai And those companies that we're talking about, they are household names, right? So let's name a few, right, these are the platforms that we all use.

Cory Doctorow Sure. Well, you know, one of the things that we're quite at pains to do in the book is to point out that there is nothing intrinsic to either tech or entertainment companies that make them better for creative workers. So we could talk about the big five publishers, which are you know, Macmillan, Holtzbrinck. Penguin Random House, which is Bertelsmann. Hachette which is Little Brown. Simon and Schuster, and so on. Or we could talk about the GAFAN you know, Google, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Netflix, it doesn't really matter. And one of the really telling sets of case studies in our book is the contrast between YouTube and how it relates to musicians. So YouTube is owned by Google. It's a giant media company that intermediates between musicians and music fans, and it gives musicians an extraordinarily bad deal. And Spotify, which is owned by the big three labels, Warner, Universal and Sony, which gives a different but equally terrible deal to musicians. And it really shows you that the problem of intermediaries isn't some failing of the moral character of people who engage in a certain kind of business, it is rather the somewhat inevitable outcome of firms that are neither constrained by competition nor by regulation, they will always find ways to gather advantage to themselves to the detriment of other parts of their supply chain.

Rebecca Giblin I might mention that Universal is the only one of those big three record labels that hasn't divested itself of at least part of the ownership stake. But you can still see from the fact that, you know, originally, all three of them had that ownership stake. And that created this really extraordinary conflict of interest, whereby they were on the one hand supposed to negotiate on behalf of the recording artists, the artists that they represented, to get the highest possible royalty rates. But on the other hand, they were owners of the company, and it was going to go to IPO. And they had an interest in making sure that that, those royalties were as low as possible so that the shares would pop on once it was listed. And now we've got this like, mixed situation where some of them have divested, Universal hasn't, and a really, really interesting ecosystem with all of these conflicts inherent. But the one thing that is really clear, and we see this in the book, we trace decades of malfeasance in the recording industry. One thing that is clear, is that whether it's Spotify, whether it's the big three record labels, whether it's Google, YouTube, all of them, none of them are trying to do what's best for artists and for audiences. They're all trying to maximise the money that ends up in investor pockets.

Sandra But is this a kind of a bigger structural change over the past 50 years? For most of human history, we're focused on people as producers, as makers of things, right, farmers or craftsmen or artists. But over the last kind of 40 years, there was this big shift towards thinking of people as consumers rather than as maker of things. So the ecosystem that you're describing, one could argue, well, it's great if you're a consumer, you don't have to pay for anything, anything is almost free. But on the other hand, this shift has kind of left artists in no man's land, right, with no revenue, no way to influence the system. And the story that you're telling is not one of the, you know, the starving artists that need to rise up, but it's of a really deep structural change that needs to happen.

Rebecca Giblin Yeah, that's right. And one of the things that we do in this book is we show that creative workers, and audiences, and workers in other fields are classed allies, because we are all suffering under these chokepoints that see more and more value being extracted from our labour and directed towards other people. And language does matter. We know there's so much literature around this. And it's fascinating that whether you call people consumers or citizens, it will actually change their behaviour. And Cory has a really beautiful term that he uses sometimes when we're talking about this, the idea that we are more than mere 'ambulatory wallets', you know, which is what is suggested by the notion of consumer, we're so much more than that. And that calling us consumers, treating us as consumers, and getting us to think of ourselves as consumers, lops off really important parts of our humanity. And in this book, we've really got a call for action, not only on, you know, we've got detailed technical proposals in here, things that we can really do to open these chokepoints out and to make things different, but we are also sort of calling for a more holistic view of humans and for humans to see each other in that more holistic view.

Cory Doctorow Yeah, I mean, the rise of the view of the most important actor in a policy sphere as the consumer, coincides with the rise of something called 'consumer-welfarism', which was a major shift in the way competition law was practiced, about 40 years ago, during the dawn of neoliberalism, it comes out of the University of Chicago School of Economics. And the idea of posing people as consumers, and only attending to whether people are paying less for goods, has a lot of significant problems. I mean, the obvious one is that you're also a worker, right. And so if the ways that prices are being made to decline is by eroding your buying power by suppressing your wages, then you know, what we care about is not the relative price of goods, but the absolute wealth of people who participate in the economy. And if you can afford fewer goods at the end of the day, it doesn't matter what the price tag says. But there are other problems as well. You know, if you care about democracy, and accountability, and sound regulation, one of the things that that requires foundationally is that the referees in the game, the regulators, have to be more powerful than the players in the game, then the regulated industries. And when firms consolidate, when a sector dwindles to just a handful of firms, they can wield extraordinary power over their regulators, they can become, effectively, rather than participants in a truth-seeking exercise when a regulator seeks to regulate, they can become bidders in an auction for what the truth will be. And so this produces poor regulation. It produces a kind of political nihilism, you know, people become less confident that their political institutions can serve them, because their political institutions fail them. You know, one area where we've seen a lot of market concentration is pharmaceuticals. And during the pandemic, there was a lot of scepticism towards vaccines and the kind of epistemological case for being sceptical towards vaccines, is pharma companies are hugely concentrated, their regulators are ineffective, and they take profits at the expense of the health of the people who use their products. That's not untrue, right. Anyone who lived through the opioid epidemic understands that that's not untrue. I am vaccinated five times; I believe in vaccines. But I think that it is not an unreasonable thing to say that you don't trust pharma regulators after 800,000 Americans die in an opioid epidemic. And so this is another way in which consumerism is inadequate. And then the final way in which consumerism is inadequate, Rebecca alluded to this idea that you're not an ambulatory wallet, if your job is to vote with your wallet to attain the policy outcomes you want, then we are saying that the people whose wallets are thicker should have the most votes. And again, if you want to erode the idea of confidence in democracy, you could do no better than to say that your influence in the world, in every sphere, not just the economic sphere, but also the political sphere, is limited to your ability to make someone hungry for your spending power, that then you could do nothing better than to orient our political sphere around consumers and not participants in the political action.

Kai I want to ask about the way in which these platforms that we all use, almost exploit this vicious cycle of driving down wages and prices because, and you have this in your book quite nicely, the Audible example of returning books, from a consumer point of view, all of this seems great, right? So they make us as consumers complicit in all of this by driving down prices by offering all these services that are then exploitative of creators. So it's very hard to enlist consumers to speak against this when the platforms are seemingly looking after the consumers. The table's turn when we think about citizenship, right. But as consumers, they try to treat us well, right?

Rebecca Giblin I might push back a little bit against that because the platforms are also very careful to hide what they're doing from individuals, even from consumers, right? So, yes, while they label us as consumers. And while we do know that that does, as I said, like that does change the way that we behave, people still have a really strong inherent desire, that the artists who make the things that they love, get, you know, treated with dignity, and that they assume that they're getting paid for their work, they assume that they're doing the right thing when they get a Spotify subscription instead of downloading music without a licence. And, in fact, people get really quite disheartened in my experience, when they find out, well hang on a minute, I've read your book, I thought I was doing the right thing. But then they're just like, well, there's nothing I can do then, right. And like, this is exactly the position...

Sandra We did buy your book on Kindle, so...

Cory Doctorow But I don't think anyone ever bought a book on Kindle, or in any other format, because they wanted to make sure that Jeff Bezos was well looked after, right?

Rebecca Giblin Exactly, exactly.

Kai So that would have been the next question. The complexity that these platforms create on top of the concentration that they have make it very hard to understand, for consumers and for policy makers, how they actually work, how they appropriate rent, how the model works? And who actually gets what share of the price?

Rebecca Giblin Yeah. And that's why we pulled the curtain back in this book, like we went through a whole bunch of different creative industries. And we're like, well, this is what they're doing here, this is what they're doing here. And it's always the same playbook. Yes, it is complex in some ways. And the complexity, again, feeds these chokepoints. So for example, there are lots of incredibly talented, driven, clever people who want different ways to make money for recording artists, but they're unable to do so because the complexity makes the entry fees so incredibly high, as well as the fact that you've got these big three record labels that control 70% of the global recorded music market, and they own the music publishers that control 60% of the global song rights. So the complexity works in their favour. But it's not actually that hard though, right, like we've pulled it apart in the book. It's not that policymakers can't get their heads around it, it's that all of the lobbying money is to say, look the other way, and there's nothing to see here. And that's why, as citizens, we have to demand better, right? We can no longer accept a policymaker saying, oh, okay, sure, artists aren't gonna make more money, so we're going to give more copyright. Because that's like giving a bullied kid more lunch money, okay? It doesn't matter how much lunch money you give the bullied school children; they're still going to be shaken down for it at the school gate. And so what we've got to do instead is give them guard dogs. If we're going to give more rights, how do we secure those to creative workers so that they actually benefit instead of allowing them to be used as stalking horses to mask other people's economic interests. And the reason why it's so effective, like when you see arguments for more copyright, it's never framed as oh, Jeff Bezos needs more money, or the record labels need more money, or anything like that. It's always framed in terms of the interest of the creators, right. And the reason why they do that is because those calls are powerful, because we do want them to get paid. Okay? So what we have to do is just take it one step further and say, you know what, we actually mean them. And we're going to hold you to account and make sure that your policy interventions don't actually harm them.

Cory Doctorow And I think it's a mistake to assume that they won't harm consumers as well, right. So when they cornered the market, they will do things to lower quality and raise prices. And the fact that they, when they have cornered the market, are also able to capture their regulators means that it'll be hard to stop them. So Audible has managed to bring all of the audiobook suppliers to heel, and now they're putting ads in paid-for audiobooks, right, which is definitely to the consumers detriment, it's taking a surplus away from consumers and giving it to Amazon. You know, Uber has raised the price of a ride, and lower the compensation for drivers. And they obfuscate both to the point where drivers who are discovered by Uber to have installed the rider app, who then use the rider app to find out what a ride that they're driving on is costing the passenger, are struck off. And you know, robo-fired from Uber. Generally speaking, I think it's a good rule of thumb, that if a firm won't tell you how their business works, it's not because they know that you're going to enjoy it. and they don't want to ruin the surprise. It's that this is because they know that you'll be angry at them.

Sandra So I think for me, there are two things we need to do here. One is structural changes, and you outlined those in the book, how do we think about putting guard dogs in place? The second is kind of lifting the veil for consumers. I think for many people, the narratives are still imposed by the same corporations that disservice artists, and in the same way that we used to think of antitrust legislation as something that is about citizenship, and that is about undue power, but then at a particular point, and I am a lapsed economist so... At a very particular point in history we did make it about consumers and about selling prices for consumers. And that is a narrative that we can't seem to be able to shake off right now. How do we think about changing the narrative as well as doing the structural changes?

Rebecca Giblin So that's the thing, right. These firms who have extracted these extraordinary profits on the back of all of these strategies that we've been talking about, have entire teams of storytellers whose job it is to frame this in ways that sell it to everybody else's...

Kai We're just a platform.

Rebecca Giblin We're just the platform, or we're here to help artists, or, you know, whatever it happens to be. And I want to throw this to Cory. Cory, you're the storyteller in our team...

Cory Doctorow So I think the most important thing here is to not let them get away with conflating the benefit that they deliver with the harms that they impose. Right? Google wants you to think that, like, some guy came off a mountain with two stone tablets and said, Larry, Sergey, stop rotating your log files and start mining them for actionable market intelligence. Google was a non-surveilling search engine. In fact, the foundational paper that Google was built on, Brin and Page wrote the PageRank paper, says that we shouldn't build advertising-based search engines because they will inevitably be corrupted and undermine search quality. There's a great Matt Bors comic, Mister Gotcha, where someone is holding an iPhone and they're typing things should be somewhat better. And this bro pops up out of a manhole and says, and yet you are typing that into an iPhone. Very interesting. Yes, I have very smart, right, this idea that the problem with the iPhone is that it gives you a way to talk to other people, and not that it's made of conflict minerals. Now that there are extractive arrangements in relationship to its suppliers, not that it locks in surveillance, not that it denies you technological self-determination, right? That idea is a wholly manufactured narrative, I'm very interested in stories of people who seize the means of computation, right, who take the part of the device of the system that serves them well, and eliminate the part of the device in the system that is detrimental to their interests. The problem with Amazon isn't that Amazon makes it easy to find a wide variety of goods, right. The problem with Amazon is the exploitative relationship, starting with their suppliers, but all the way to the, you know, guy sitting in a bag and a delivery van, because he'll get his pay docked if he goes to the toilet in a regular bathroom. You know, those are the problems. I am fully prepared to believe that we could build a service that can reliably deliver products to us that don't involve anyone shitting in a bag. And I dare anyone to prove me wrong.

Rebecca Giblin Can I just say one final thing, I feel like we've talked a lot about the problems here and how tough everything is. And people listening to this might be feeling just like, uughhh, again, a little bit hopeless, which is a reaction that we've sometimes had. Especially to people who've just read the first half of our book, they've got so full of rage. I wasn't actually expecting the rage, Cory. People to be as angry, because we've worked in this for so long, we sort of knew it was this bad. But other folks who maybe just worked in one of these industries, they knew how bad it was there. But then they read all the rest. And like there was like a, a kind of red mist rage, but also the despair rage where you then just throw it against the wall and you're just like I can't read any further.

Sandra Next to the climate change books.

Rebecca Giblin Yeah, with the whole oeuvre of Naomi Klein. And I just want to emphasise, if you get to that point, keep reading, because this is actually I think, a really hopeful book. We were just determined this wasn't going to be yet another these chapter 11 books, where it's 10 chapters about how terrible everything is, and then some hand waving at the end that's like, oh, well, too bad we've run out of time, but maybe, like, vote harder. And so we do have all of these really detailed proposals about what we can do to widen these chokepoints out, but much more broadly calling for a movement around this, and looking at how we can work together, how we can reintegrate ourselves as whole humans and not just ambulatory wallets, and actually fix this, and save the world.

Kai And I think it's especially important that, you know, we talk about this in the context of a business school because systemic change has to start with education, has to start with actually knowing what's going on and actually lifting the veil and sort of unpacking, or discarding a little bit, the narratives that we're used to, that then make us so surprised at the reality that you outlined in your book.

Cory Doctorow Well, thank you.

Kai Thank you, Rebecca. Thank you, Cory.

Cory Doctorow Thanks.

Kai Very much appreciated.

Sandra Thank you so much.

Outro You've been listening to The Future, This Week from The University of Sydney Business School. Sandra Peter is the Director of Sydney Business Insights, and Kai Riemer is Professor of Information Technology and Organisation. Connect with us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and WeChat. And follow, like, or leave us a rating wherever you get your podcasts. If you have any weird or wonderful topics for us to discuss, send them to sbi@sydney.edu.au.

Close transcript