Coping with being captive at home

Billions of people are now in self-isolation for an indefinite period. This is the largest mass incarceration of people the world has ever seen. So what problem does this create and how can people cope?

Research on long-term captivity in prisons shows inmates experience, boredom, loss of emotional relationships, loneliness, stress, leading to anxiety, depression, anger, and phobias. People on polar expeditions can also suffer disturbed sleep, impaired cognitive ability, negative affect, and interpersonal tension and conflict undergo psychological changes.

Even short exposure to captive contexts, such as airline delays, can lead to physical discomfort and anxiety, frustration, or even panic as well as: boredom, fear, disturbances from others, health problems, not looking as good as usual.

At home isolation is a form of ‘cabin fever’ which includes feelings of dissatisfaction at home, restlessness, boredom, irritability, and needing to break routine.

Fortunately, research also tells us there are ways people cope with stressful events.

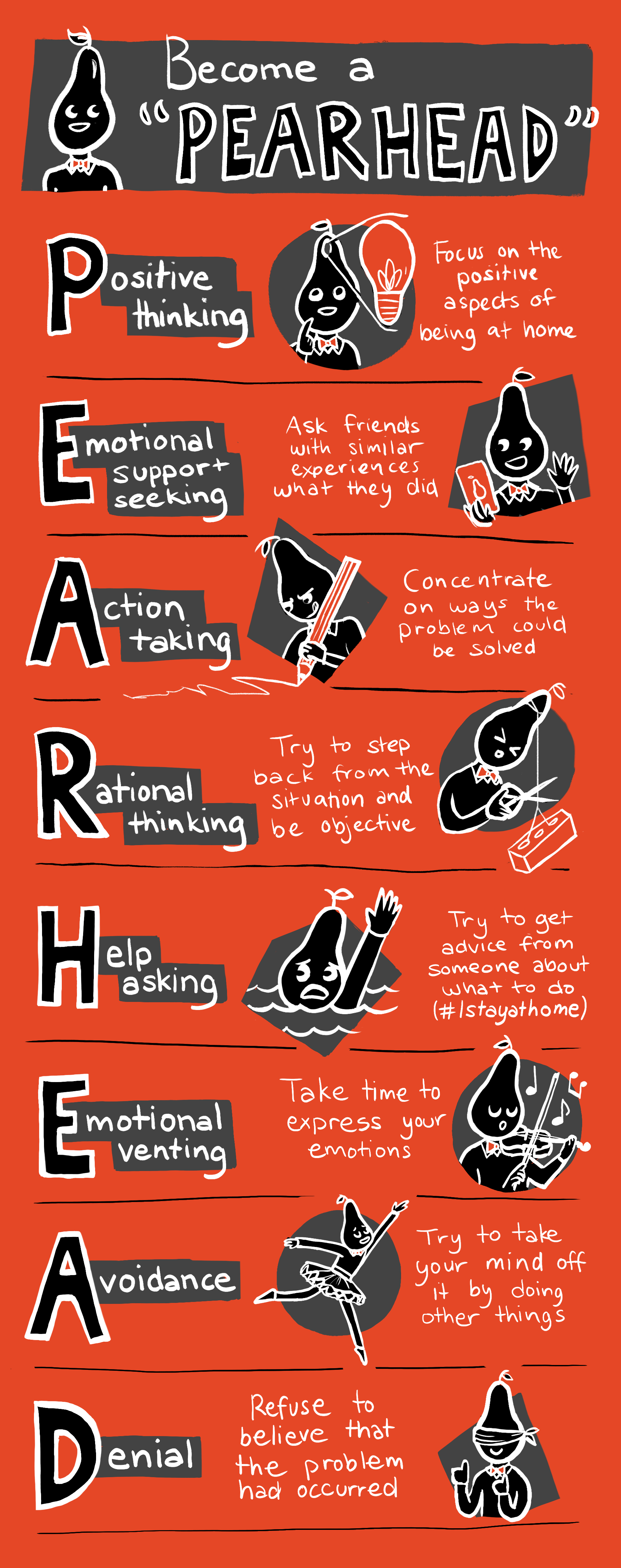

Become a PEARHEAD

Positive thinking: focus on the positive aspects of being at home. Try to make the best of the situation, e.g., 6 hashtags to stay positive or look for positive and hopeful stories of local people who have experienced COVID-19.

Emotional support seeking: stay connected and share your feelings with others you trust and respect. Ask family friends with similar experiences what they did or contact Lifeline (call 13 11 14) if it gets bad.

Action taking; concentrate on ways the problem could be solved. Try to make a plan of action. Follow the plan to make things better and more satisfying. Some productivity actions include; being more focused at work if you are working from home, and working on personal development or house development projects.

Rational thinking: try to keep your feelings from controlling your actions. Try not to constantly watch the news and avoid listening to or following rumours that make you feel anxious. Instead, seek information updates and practical guidance at specific times during the day from health professionals and WHO.

Help asking: ask friends with similar experiences what they are doing.

Emotion venting: recognise it’s normal to have mixed feelings and take time to figure out what you are feeling. Realise that your feelings are valid and justified. Allow time to express my emotions. E.g., negotiate 20 mins ‘rant time’ a day with family and friends where you can all share emotions without judgement.

Avoidance: try to take your mind off COVID-19 by doing other things. Distract yourself to avoid thinking about it and find satisfaction in other things, e.g., spend more time planning and preparing healthier meals, spend extra time on body care regimes such as moisturising, grooming, and exercising.

Denial; if all the above fail some days, then denial might be useful as a last resort. Deny that isolation is happening and refuse to believe that the problem had occurred. Catch up on sleep, siestas and the occasional drink.

The takeaway is that to manage a new norm, a new way of living requires several physical and mental adjustments and coping research (being a PEARHEAD), can help us survive in this new normal. Although more is better, you can choose as many or as few coping ways as suit you and your situation, but there are a wider range of self-help options available than people might imagine. If we get used to practising them now, they may even provide us with a better way of coping with the whatever normal is after COVID.

This is part of a series of insights related to Coronavirus (COVID-19) and its impact on business.

Image: Catherine Cordasco. Submitted for United Nations Global Call Out To Creatives.

Vince Mitchell is Professor of Marketing at The University of Sydney Business School. He did his PhD in Professional Services Marketing at Manchester University where he became UMIST’s youngest Professor.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.