Sydney Business Insights

Nudging towards happiness

“Economists are not that smart!”

When the winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics kickstarts a webinar – hosted by a Business School – with this statement, you might suspect he is being disingenuous.

However, Professor Richard Thaler has spent his career challenging mainstream economics.

Professor Thaler’s main target has been destroying the character of ‘Econs’ (Homo economicus, the perfectly rational economic agent) and replacing it with, well, us. Humans. Beings who find it difficult to do maths in our heads, who frequently fail to make the best financial decisions, are too lazy to fill in forms that would set up a savings plan for our retirement, neglect to do the small things that would minimise credit card debt or choose the most cost-effective mortgage. (OK that last one is actually very hard.)

Professor Thaler investigates how people really behave – not just around financial matters, but in many aspects of our lives (what we choose to eat, if we exercise, how safely we drive).

Professor Thaler is credited as the ‘father’ of the most significant development in economic thought for the last 30 years, behavioural economics, (hence the Nobel Prize).

Feeling economics

Behavioural economics is the study of empirical observations of human behaviour around the decisions people make where there is an economic outcome.

If this is sounding like psychology rather than the study of markets, it is because Professor Thaler and his fellow behavioural economists investigate situations where humans are not acting ‘rationally’ (i.e., not in their best interests) and then come up with a strategy that will help people make better decisions.

Professor Thaler calls this process nudging.

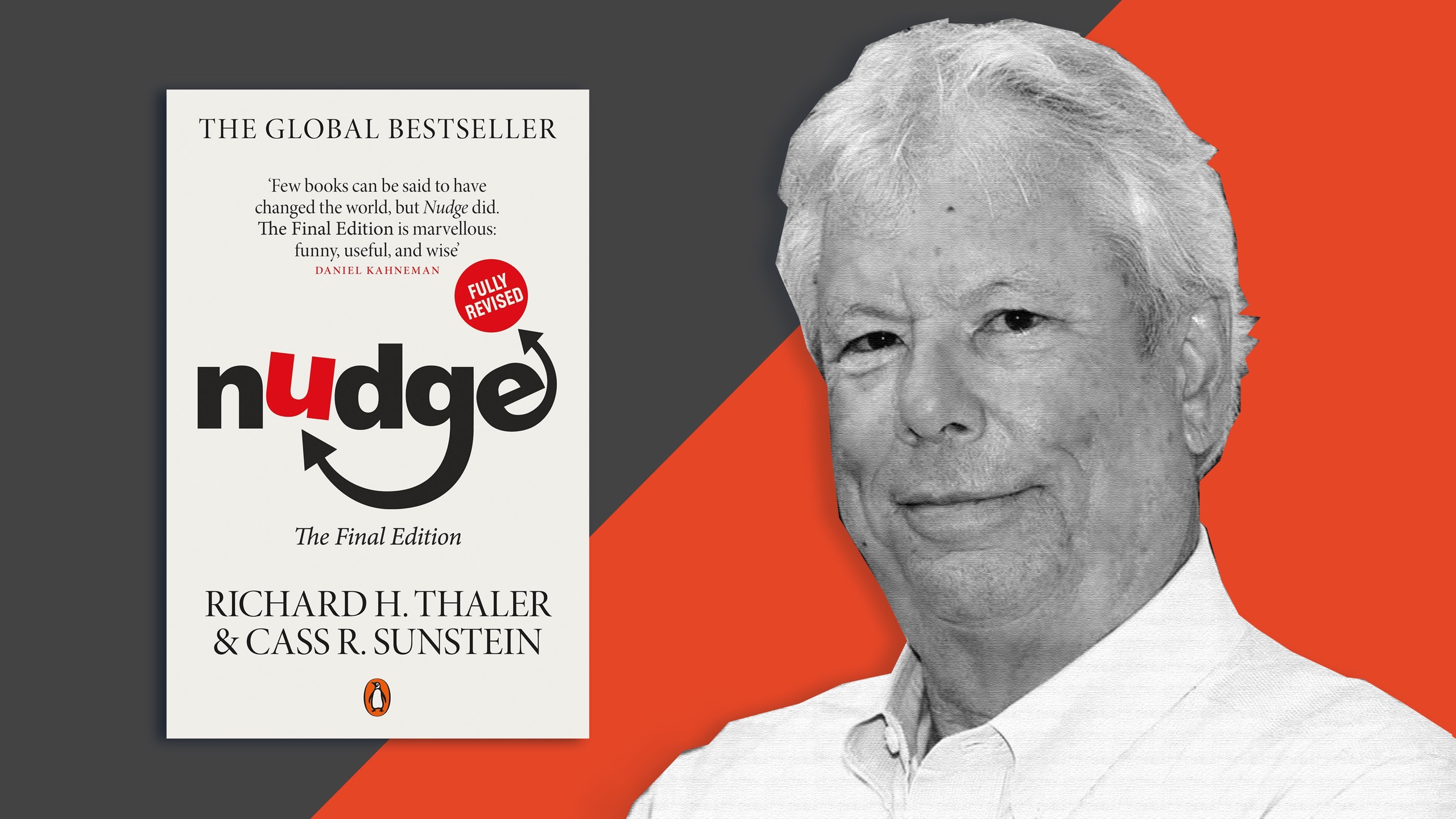

Together with Professor Cass Sunstein, Professor Thaler has written two books dedicated, as they put it, to helping people live happier and healthier lives: Nudge (2008), and now Nudge: The Final Edition (2021).

In the webinar, Professor Thaler explained a nudge is:

“Any small feature of the environment that attracts our attention and alters our behaviour. And it does so without requiring anyone to do anything. And without economic incentives. So, the rational economic actors and economic models would not be affected by nudges. But humans are.”

A helping hand

The concept has been wildly successful: more than 400 ‘Nudge Units’ have been established in governments and businesses around the world. (Usually these are less exotically named Behavioural Insights Units.) The Australian Government has a high-powered one nested within the office of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. In 2010 the British Government established one of the first ever Nudge units, now a social enterprise with operations around the world.

Professor Thaler agrees he and Professor Sunstein did not invent nudging:

“We all use nudges all the time in our daily life: we set an alarm to wake us up in the morning. We don’t have to set an alarm, we don’t have to get up. It’s just a nudge. We have a calendar invite to remind us that we have a webinar at seven o’clock my time. We put money aside into an account that we label retirement money. All of these are nudges that we do to ourselves, and other people are nudging us all the time, for good or for bad.”

What Thaler and Sunstein did was recognise the systemic way people misthink – we do it frequently enough there is enough evidence to reveal a pattern. There are many reasons for human misjudgement – being too optimistic, loss aversion, relying on heuristics, the availability bias, too many choices.

A path through the Amazon

Thaler’s life work is to identify the environment that will encourage us to make the best choice – the one that is, either financially or health wise, unambiguously the better path.

Thaler calls this ecosystem ‘choice architecture’.

“Think about the Amazon storefront, which, of course, is just a web page. Now, they have essentially every book in print anywhere, and some that are out of print. If you went into a physical store that had that you would run away, it would just be horrible. And you could certainly never find anything – how would they have it organised? Now a small bookstore, you know, can be fiction, non-fiction, whole section devoted to nudge presumably. But the reason why Amazon or Netflix can operate on the scale they do is they have good choice architecture, meaning people can find what they want. And we encounter choice architecture everywhere. If we go to a restaurant, someone has decided what food will be cooked, someone else has decided how to write that down on a menu, how to group things, how to order things.”

Super made easy – well, less dense

His most famous choice architecture creations are the nudges Thaler recommends to encourage enrolments in pension saving plans, particularly in countries without compulsory superannuation. Saving for retirement is, as Thaler and Sunstein point out in Nudge, one of the most difficult tasks Humans face. (The computation is very hard and it takes considerable self-discipline). Plus, as a species we have not been doing it very long – retirement being a very latter-day concept.

Superannuation nudges can occur in several ways: companies can ask people to nominate a savings plan at the same time they sign onto employment or people can be automatically enrolled into a savings plan that they would consciously have to opt out of. Savings plans come with various features: what is the default savings rate, are there employer contributions, stepped up savings ratios? But overall, the best designed plans ensure a decent post work income stream with no additional debt burdens.

Vaccine refusal and other nudge limits

Nudges are not ‘shoves’ – for Thaler choices must be voluntary, easy to do and cheap to avoid. Hence taxes, fines subsidies or bans are NOT nudges. For Thaler making COVID-19 vaccines easy to obtain – for example offering lots of vaccine services, taking vaccines to where people work or live – these are all good nudges. However, the vaccination debate is also a good example of the limits of nudging. Thaler’s employer, the University of Chicago, has mandated vaccination on the part of all employees and students.

“I think we are past the point of nudging when it comes to the vaccine. And the reason for that is vaccinations are a simple case of an externality. If you’re unvaccinated, you can make me sick… you can make your students and colleagues sick. And you don’t have the right to make me sick.”

Sludge and other bad… paperwork?

Recently Thaler has turned his attention to nudge’s ‘evil twin’ – sludge. Thaler defines sludge as anything that makes it harder for people to obtain an outcome that will make them better off. Lots of paperwork to receive financial assistance or a rebate to which you are entitled, having to navigate a baffling website to get a COVID vaccination, a two hour wait for customer service.

“I do think every organisation, particularly large organisations, should go through a sludge-mediation activity. And I think they could save a lot of money and buy a lot of nice bottles of wine”

Watch the full event

Sydney Business Insights is a University of Sydney Business School initiative aiming to provide the business community and public, including our students, alumni and partners with a deeper understanding of major issues and trends around the future of business.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.