Do innovation centres undermine innovative thinking?

**As rights to this article belong to the original publisher, AFR BOSS Magazine, please contact AFR for permission to republish.**

Despite claims that up to 90 per cent of innovation centres fail and end up being a massive waste of resources, more and more companies are setting up centres, labs and hubs to drive innovation.

“In the past, innovation was considered subversive, disruptive and a challenge to the established order,” says Dirk Hovorka, associate professor and chair of the business information systems discipline at the University of Sydney Business School.

“As economic logics came to dominate, innovation metamorphosed into its current focus on commercialisation of products.”

It used to be a select few companies, in the style of Silicon Valley greats, that tried to harness the promise and accelerate the discovery of disruptive technologies or business models through innovation centres. Now, innovation is something of a holy grail that every forward-thinking company needs to chase.=

Innovation centres have been welcomed because they provide resources, including physical space and funding support, for fledgling ideas, products and services, as well as providing an interface with clients or organisations. But there is tension inherent in the creation of “safe” innovation spaces. The innovation centres come at the risk of losing the one thing that makes innovation so exceptional: its “wildness”.

The idea is that innovation centres can give organisations an edge by allowing them to conceive new products and ideas. The centres are intended to be beneficial on a number of fronts, including financial performance, corporate brand and even employee engagement.

“While innovation centres are becoming popular in Australia, it’s not clear they are delivering on their aims,” says Hovorka.

A Capgemini report claimed that “about 80 to 90 per cent of innovation centres fail, and end up being a massive waste of resources”.

Even fintech accelerators, considered to be among the most innovative of centres, have yet to fulfil radical innovation promises. A recent study of fintech innovation labs in New York, Hong Kong and London showed that even with funding from several banks, they remain on the sidelines of disruptive ideas and simply carry on vetting sustaining innovation projects.

“There is growing scepticism in the commentary around innovation centres, but currently there is not much in the way of academic analysis of their role in making organisations more innovative,” says Ella Hafermalz, a postdoctoral researcher in business information systems at the University of Sydney Business School, who is interested in how businesses harness new technology and ideas in order to work differently.

So, what are innovation centres?

The answer seems straightforward: “Innovation centres are sectioned-off parts of an organisation that are dedicated to driving innovation,” says Hafermalz. Two common types are in-house innovation labs that sit inside an organisation, or innovation outposts that are based in universities or industry centres such as Silicon Valley.

In-house innovation labs sit within an organisation, but are separate, such as the Commonwealth Bank’s CommBank Innovation Labs.

These are sectioned-off areas that showcase the bank’s latest products and provide tools for employees and visitors to work with the bank to generate new products and ways of thinking. There are three labs, one in Sydney, one in Hong Kong and one in London.

Innovation outposts based in universities or industry centres, such as Nestle’s outpost in Silicon Valley, locate a small team from an organisation in an external innovation centre to ensure they are involved in the tech community without the investment of moving company headquarters.

Hafermalz notes that there are also other types of innovation centres, albeit less common: community anchors, such as the Allianz Digital Labs program or the USYD Incubator where start-ups partner with mentors to test their ideas to community. “They are good for attracting venture capital and solutions can be developed and tested with minimal investment,” says Hafermalz.

University residences, such as Cisco’s innovation centre dedicated to the “internet of everything” in Western Australia’s Curtin University, try to take advantage of university campuses where innovative solutions can be produced then extracted for use in the business.

In every circumstance, innovation is given a dedicated, but separate space. Innovation is idolised yet excluded. “Innovation is seen as something that needs to be produced and yet simultaneously something the organisation needs to be protected from,” says Hovorka.

All hubs great and small

“We looked at the way in which innovation centres are frequently constructed and noticed their physical and cultural separateness. We drew from that the analogy that these are akin to wildlife reserves in Australia,” says Hovorka.

In his 1980 essay, “Why look at animals”, the English art critic John Berger talks about how human-animal relationships have changed over time. Although we once used to be close with animals, the industrial revolution changed that relationship. As life began to revolve around city centres, we put animals into separate places, including into reserves and farms, kept them as pets and showed them off in zoos.

It is this thinking that Hafermalz and Hovorka use to examine innovation centres as a way of separating the “wildness” of innovation from the rest of the organisation. The centre “contains” innovation within a safe enclosure, much in the same way animals are separated from society to keep them safe and to keep society safe.

But in separating animals from society, nature has been rendered toothless in relation to man, writes Berger. Hafermalz notes that innovation may be headed in a similar direction in attempts to “tame” it inside an innovation centre.

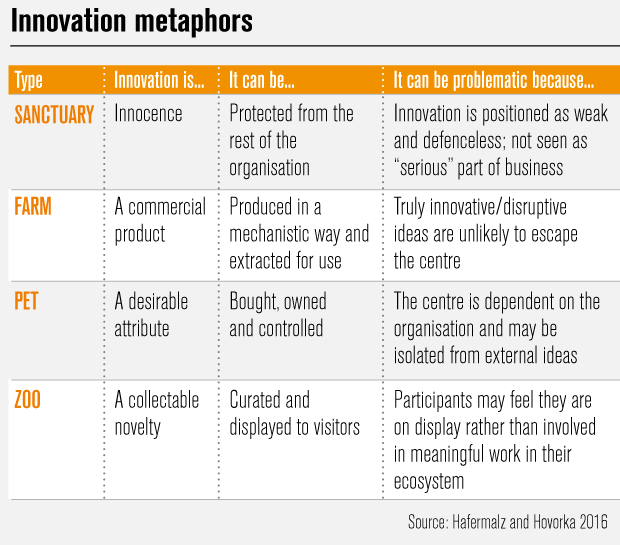

Hafermalz and Hovorka use four metaphors to explore the idea of trying to keep what was once considered wild in a safe enclosure: a sanctuary, a farm, a pet and a zoo.

The analogies help highlight a number of potentially problematic issues with innovation centres.

If we look at the innovation centre as a sanctuary, this is where innovative activities and people can be protected from the rest of the organisation. “This can be a good thing,” observes Hafermalz, “as new ideas and products perhaps do need protecting from commercial interests, at least in their initial years.” But this also incurs the risk of innovation being positioned as something that is weak and defenceless and not a serious part of the business.

Large-scale farms have separated animals from the everyday life of society and have treated them as a commercial product, selectively extracted when useful for humans. Likening the innovation centre to a farm highlights it as a place where teams are put to work to produce innovations that can be extracted only when they’re seen as being safe and useful for the organisation.

Hafermalz points out that this may seem appealing to organisations that want to streamline innovation activities, but if ideas and products can only “escape” into the real world when they’re considered to be safe, what is the likelihood of their being truly disruptive? This marks a shift from being innovative to managing innovation.

Another analogy is pets, which are a relatively new way to relate to animals. Berger says that we keep pets because we have elements of our personality that we are insecure about that pets can help relieve. Using the metaphor to think about innovation centres, “brings up the idea that perhaps innovation centres are there to furnish an aspect of the organisation that they are insecure about,” says Hafermalz. “The innovation centre can reassure the organisation that they are in fact innovative. The organisation can even show it off to visitors and say ‘Look! We have an innovation centre, we’re an innovative organisation.’ ”

As a “zoo”, innovation centres create an illusion of wildness, yet the zoo eliminates the spontaneity and vitality of real life. “This led us to think about how innovation centres are a place where curiosities are collected, both in terms of new technologies, unusual activities and people, and then curated and displayed for the purpose of being shown off to external visitors,” says Hafermalz. Being treated as a spectacle could diminish the capacity for those involved to challenge the status quo for fundamental disruption.

Disparate connections

Is the emergence of “enclosed” innovation centres a negative thing? Such centres have the potential to be beneficial for financial performance, corporate brand and even employee engagement. This is good, but they’re innovation with the small “i”, says Hovorka. “Centres might play a role in protecting the more vulnerable parts of the process, or to get a range of people and organisations together to work on common problems, but as soon as this is just about making innovation safe you lose the really disruptive potential of innovative ideas.”

“There are some very positive examples of innovation centres that produce a counter narrative,” says Hovorka.

This seems to come from centres that are deliberately networked with other centres and organisations. Hovorka notes, “They are very much networked with other centres, they’re location-based, they go outside the organisation and interact with outside entities and ideas, and serve as a place of circulation of people and ideas. Innovation is not something that we want to try to tame.”

Perhaps more fundamentally, this points to the need to question our assumptions about how innovation happens. We tend to assume innovation is basically a linear process, the outcome of predictable, manageable stages, when in practice substantive innovations – think iPods or Uber – have relied on making disparate connections between ideas, products and services.

Innovation centres continue to grow and multiply. Last month alone Morgan Stanley launched a multicultural innovation lab, Boeing opened an innovation centre at The University of Queensland, Ford opened one in east London and Ferrero opened a food innovation lab in Singapore.

To serve a transformative function, innovation must become “a bridge between the world as we know it and a future state of affairs whose outlines are emerging. But we can only move towards new worlds through openness to what is wild and dangerous,” Hovorka says.

This content has been produced by Sydney Business Insights in commercial partnership with AFR BOSS magazine. Read the original article.

Dr Sandra Peter is the Director of Sydney Executive Plus and Associate Professor at the University of Sydney Business School. Her research and practice focuses on engaging with the future in productive ways, and the impact of emerging technologies on business and society.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.