SDGs by 2030 – are we on track?

Ending the wild west of data collection

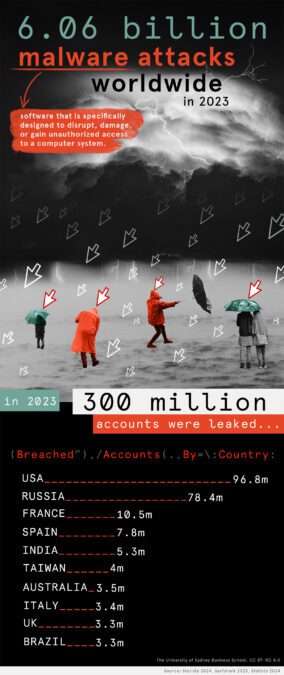

Cybercrime attacks both individual and the national well-being.

Having information stolen in a data hack can mean identity theft, loss of assets and considerable effort reestablishing peoples’ online identity and real-life reputation.

Such violations are hugely psychologically distressing and can lead to strong feelings of unease and a lack of trust in institutions. Which is an entirely reasonable response – a data hack is a form of attack and your well-being is at stake.

Sturdy infrastructure is the hallmark of a well-managed economy. Cyber breaches – consider just a few of the recent hacks into the banking, electricity, and phone networks – undermine confidence in business systems. Trust is an important element in business. If trust in the integrity of the internet is significantly undermined it could crash not only entire business networks, but shut down critical infrastructure and threaten national security.

SDG 9 recognises that strong resilient infrastructure, both software and hardware, is essential to our personal well-being as well as to economic development and national security. When it comes to the internet, we are still coming to grips with the range of potential new harms (for example, AI cyber crimes) for individuals, nations and global security.

I research how cyber security experts understand the risk surrounding the data they collect on their customers, suppliers and other key stakeholders. This involves understanding what they do if and when they are attacked or when their systems are breached.

Data breaches can range from your online friends’ network being sent inappropriate messages from your social media accounts to financially ruinous identity theft or having highly private medical information leaked onto the internet. How would you respond to having your medical history splashed across the web?

People’s reactions to being hacked range from feelings of anxiety to self-harm and suicide. The exchange of data across the internet needs to be safe, transparent, and accountable.

The path to greater online safety is to have less sharing of personal information sprayed across the internet. My proposal to improve online safety includes having a central ‘data information hub’ with responsibility for holding individuals’ data, such as proof of their identity.

When needed, this body could validate identification through a controlled process without the need for data duplication. This body would simply provide individual’s ID verification to other organisations. No actual personal data would be transferred.

For example, Services NSW, the state government agency providing centralised access to all government services in my home state, could be allocated this task. Other government, business and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) could then request verification from Services NSW. The hub would become the single source of online verification.

Under such a scheme people will only have to provide their details once – and this is important – to a highly secure government-backed site. Other organisations seeking proof of ID can be reliably informed but don’t get to hold people’s data. This will reduce the burden on individuals, limit the spread of personal information across the internet and remove the persistent need for websites to collect and store information about users.

Right now, it’s like a gold rush in data collection: it’s free to gather and cheap to hold. And the more data that organisations have, the more powerful each data point becomes because it conglomerates, increasing its value exponentially. The ‘mosaic’ effect of amassing troves of data – even if it is anonymised – can lead to re-identification if enough data sets containing similar information are hoovered up.

That needs to change. The ‘price’ of holding data needs to reflect the real costs of potential harm to individuals.

Organisations need to take data collecting and storage responsibilities more seriously and be punished both reputationally and financially if they are hacked and their client’s information stolen. A better set of values needs to be put on people’s data so it is not seen as just a ‘free’ good but carries a considerable cost if that data is violated by a bad agent.

Under the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme, organisations that have had a significant data breach need to inform affected customers. They should also face strong penalties, including large fines. And companies should be required to delete our data if they are no longer using it (if we cease to be their customer, for example). Happily this is being considered in the current Privacy Act Review.

Unlike compromises to other forms of infrastructure such as electricity, or roads, or rail, which are sovereign based, data breaches are often international and deeply interconnected through 3rd party and other commercial agreements. This means IT protections and standards need to be standardised and agreed between nations. International protocols are needed.

It’s important that individuals also take more responsibility for their online safety. Unfortunately, the whole system is geared at tricking us into giving information, which automatically puts us at risk.

Be more suspicious and more educated when it comes to cyber issues, manage your passwords better and know how to customise settings.

Change will only come when people’s outrage is channeled into legal and regulatory change. We also have to overcome data breach fatigue, where people don’t want to know anything about it. Information needs to be presented in everyday language. It has to be easy for all of us to do the right thing.

Resources

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target addressed:

Target 9.1 Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all

Max is an Associate Professor for the Discipline of Accounting at The University of Sydney Business School. His research has explored corporate accountability, ethics, identity and corporate social responsibility

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.