Tom Barratt, Alex Veen and Caleb Goods

Did somebody say workers’ rights? Three big questions about Menulog’s employment plan

Menulog, Australia’s second-largest food ordering and delivery platform, has declared it will break with the standard “gig platform” business model and engage some of its couriers as employees, not independent contractors.

“We owe it to our couriers,” Menulog’s managing director Morten Belling told the Senate Select Committee inquiry into job security this week. The inquiry is investigating the scope of insecure or precarious employment in Australia.

The Transport Workers’ Union says Menulog’s move is a “watershed moment for the gig economy”. By committing to pay couriers a minimum wage and superannuation, it is going further than its competitors such as UberEats and Deliveroo.

But let’s not get too excited yet.

What Menulog has announced is just a pilot program, offering employment to some couriers in Sydney’s CBD. How much of an overall benefit it makes even to those workers will depend on the details.

Work can still be insecure and poorly paid even when a worker is “employed”. Just ask many casual employees in the hospitality, horticulture and retail sectors.

Accepting greater responsibility

To give Menulog credit, the company isn’t legally obliged to make this change.

The prevailing independent contractor model, paying workers “piece” rates with no benefits such as superannuation and paid leave, is controversial yet thus far legal – even though it means many earn less than the minimum wage.

In engaging couriers as employees, Menulog is accepting greater responsibility for their welfare. Things like insurance and workers compensation become straightforward. As contractors, already lowly paid workers are often responsible for their own insurance.

These are vitally important issues given the risks involved in courier work. Last year five delivery riders were killed in traffic accidents. Though none were Menulog couriers, Belling mentioned this as a key driver for the company’s change.

The shift to an employment model should also result in greater income certainty for workers. But to what extent they will be better off depends on at least three important details.

1. What’s the award?

The first question is what modern award – the document that sets minimum terms and conditions of employment within a specific industry or occupation – will couriers be employed under.

According to Menulog there are “a number of challenges” in moving to an employment model, with Australia’s award system cited as a potential barrier.

The award now covering couriers is the Road Transport and Distribution Award 2020. Menulog has indicated it wants delivery workers to be covered by a new award, and intends to consult with the union to create it.

It hasn’t spelt out what the specific “challenges” in the existing award are – employer groups often talk in generalities about a lack of flexibility – but it may include removing minimum engagement periods.

Under the existing award – as with others – a casual employee must be paid for a minimum four-hour shift. Minimum engagement periods are important for giving workers some certainty as to how much they will earn when asked to work. In contrast, an independent contractor can be engaged for a one-off delivery that may only be for a few minutes to earn a few dollars.

The award also stipulates penalty rates and allowances for unsociable hours or days (such as public holidays).

If Menulog’s move involves eroding fundamental award principles about minimum hours and payments, its couriers could find “employment” isn’t much better their current conditions.

2. Does every worker get to be an employee?

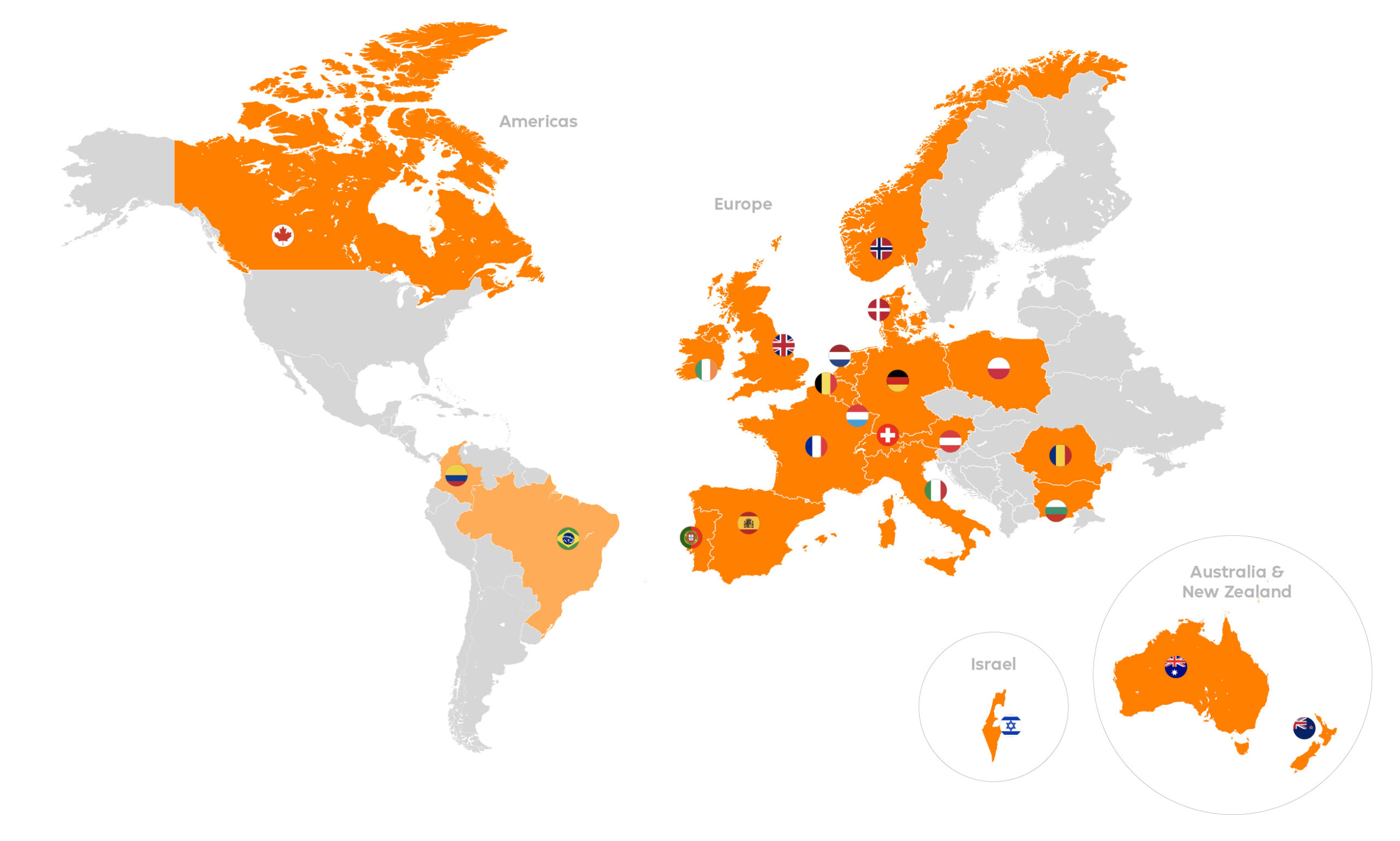

Even given the limited scope of the trial (Menulog operates throughout Australia and New Zealand, while its parent company Just Eat Takeaway operates in 23 countries) it is unclear if the platform plans to make all couriers working in Sydney’s CBD employees.

Or will it end up with a two-tier system, where some couriers are engaged as employees and other remain contractors? If this is the case, it could make contract work even more precarious.

It’s important to know who gets to be an employee and why. This should be transparent. Platform companies are notorious for their “black-box” algorithmic management. Their algorithms now effectively make workers compete with each other for gigs. A system that makes them compete for the chance to be rewarded with the badge of “employee” is hardly much better.

3. How to deal with multi-apping?

It is a feature of the gig economy that couriers often work on multiple apps at the same time to try and win more gigs – a practice known as “multi-apping”.

If they become Menulog employees, will they have to forego this right? Will they be allowed to earn money through other platforms during times when they’re not employed?

Again, these details will need to be worked out. The answer will have ramifications across the food delivery industry. Finally, are customers willing to pay?

Menulog’s announcement has been welcomed by unions, including the Australian Council of Trade Unions’ head Sally McManus. But the details that remain unclear are fundamentally important.

This trial may mark a major shift in this part of the “gig economy”. The head of Just Eat Takeaway, Jitse Groen, said last year he would rather his workers get more protections and benefits. Belling told the Senate inquiry that treating couriers as employees “may cost us more, but it’s the right thing to do”.

But how much more Menulog is prepared to pay also depends on how much more customers are willing to pay.

It is important for the gig economy as a whole that Menulog get this right in Australia. That will depend on the answers to the above questions.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dr Tom Barratt is a DECRA Fellow and Senior Lecturer in the Management and Organisations Department of the Business School at The University of Western Australia. His work as a labour geographer investigates working in the gig economy and in peripheral extractive regions.

Dr Alex Veen is a Senior Lecturer in the Discipline of Work and Organisational Studies at the University of Sydney Business School. He is a DECRA Fellow and Co-Director of the Sydney Employment Relations Research Group. Alex is an employment relations researcher focusing on the on-demand gig economy, algorithmic management, and management’s industrial relations strategising.

Dr Caleb Goods is a Senior Lecturer of Management and Employment Relations at the University of Western Australia Business School. His research examines work and workers’ lived experiences in the gig economy, as well as the transition to a greener economy.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.