Christopher Wright

The impending apocalypse happening in plain sight: a response to the latest IPCC report

If you are not horrified by the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report then you are not getting the message.

That within 10 to 15 years temperatures are likely to rise by more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. At 1.2C increase the coral reefs are gone (we’re already at 1.09C). The Great Barrier Reef is just the most potent icon in this loss category.

IPCC modelling shows the world will likely reach 2C temperature increase by 2050 unless unprecedented and radical reductions in the world’s carbon emissions are made immediately.

This level of warming would lock-in a 10-meter sea level rise over the next millennium. This would mean by the end of the century that under our current trajectory Australian coastlines would retreat by as much as 100 metres.

The data is terrifying, but this latest IPCC report is not a shock. This is the sixth IPCC report since 1988. The story is consistent and clear.

Human activity is changing the Earth’s climate in ways “unprecedented” over hundreds of thousands of years.

Economic weather watch

It is still possible to pull away from the brink: the International Energy Agency says it is possible to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 IF exploration and exploitation of new fossil fuels halted as of this year.

Individual action is well and good, but the crisis is so profound that only mobilisation at government level can generate sufficient response to turn this catastrophe around. What part of the impending global catastrophe will trigger a crisis response from governments?

The consequences of climate change are now evident in our news feeds. In early 2020 we saw much of the east coast of Australia burn in the unprecedented “Black Summer” and the Great Barrier Reef suffered a third catastrophic coral bleaching event. This northern hemisphere summer the west coast of North America has been racked by record-breaking heatwaves and wildfires, Germany and China were hit by massive floods and in the southern United States, Hurricane Ida, made landfall in Louisiana, the latest in a longline of worsening storms threatening the Caribbean coastline.

The economic consequences of climate change will only become more intense as the planet warms. As the pandemic has shown, our tightly integrated global economy is vulnerable to supply-chain shocks and extreme weather events will exacerbate this weakness.

Climate showdown

What action will the heads of governments agree on at the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, UK from October 31 – November 12?

For Australians I would advise keeping your expectations low.

Despite the incontrovertible evidence outlined by the IPCC report that the burning of fossil fuels has been the major contributor to human-induced climate disruption, the Australian Government has promoted a ‘Gas-Fired Recovery’ out of the COVID-19 recession. The answer to a crisis produced by fossil fuel energy appears to be a commitment to the expansion of new carbon frontiers!

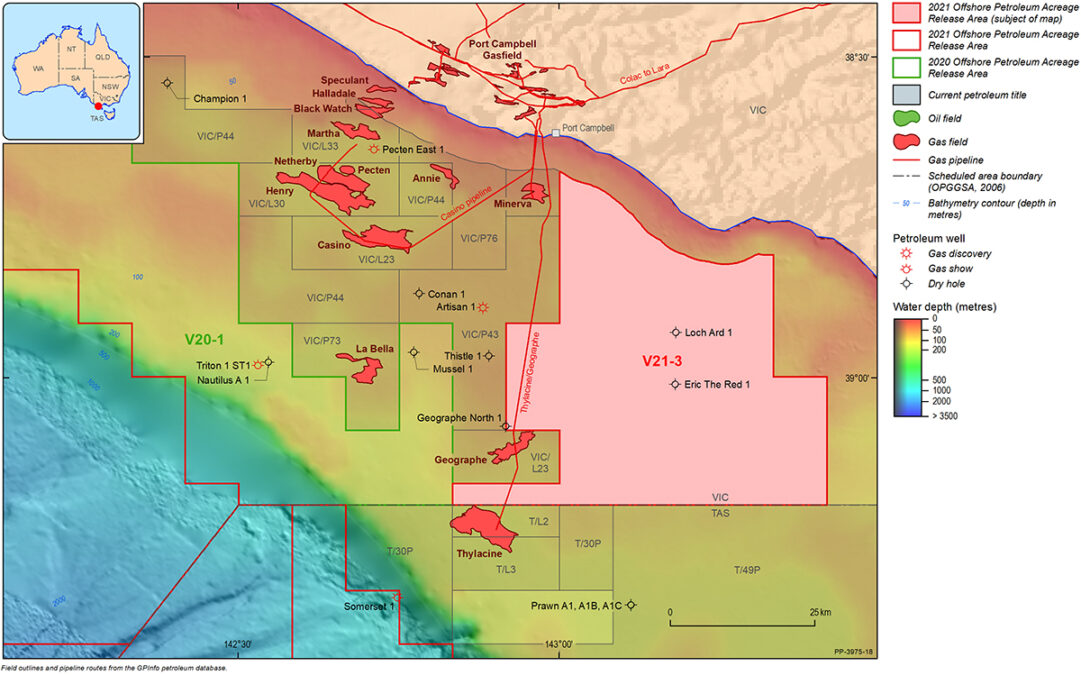

Indeed, the Government has pushed ahead with the opening up of the Beetaloo Basin in the Northern Territory for gas fracking against the opposition of Indigenous communities and recently announced 21 new areas (covering 80,000 sq km) for offshore oil and gas exploration, including some near the ‘Twelve Apostles’ off the Victorian coast.

There are still proposals to drill for oil along the coast of NSW between Manly and Newcastle.

Waiting for Techno Godot

If, like US climate envoy John Kerry, you are convinced that technologies “we don’t yet have” are going to get us to zero emissions, I am sorry but technology is not coming to save us.

The Australian Government has sunk more than $1billion into carbon and capture research over the last 20 years – and nowhere is this technology in use at scale that will make even 1% different to the level of carbon in the atmosphere.

Renewable energy offers a viable solution in decarbonising our energy needs. However it would require policy leadership akin to wartime mobilisation from governments to drive this production switch to a renewable energy future. Ironically, given its natural assets, Australia could be a renewable energy superpower, but lacks the political will to drive this transformation. Our politics have been captured by a ‘fossil fuel forever’ imaginary underpinned by political donations, industry lobbying and revolving door appointments between the coal, oil and gas industries and our political parties.

We are afflicted by what US futurist Alex Steffen terms the politics of ‘predatory delay’: Today most companies – even fossil fuel companies, no longer deny the facts of climate change. They simply argue for ‘delay, on the basis that to change too quickly would be unfair to them.’

Stealing the future

This delay has of course been the desired industry response since the “inconvenient truth” of climate change emerged politically more than four decades ago. In the reliance upon continued compound economic growth, corporate and political elites have maintained that the commitment to fossil energy was incontrovertible. We have, to quote CEO and environmental activist, Paul Hawken, an “economy where we steal the future, sell it in the present, and call it G.D.P.”

As the American writer Elizabeth Kolbert has noted: “It may seem impossible to imagine that a technologically advanced society could choose, in essence, to destroy itself, but that is what we are now in the process of doing.” We now live in an age of consequences in which the debt of a small part of humanity’s carbon profligacy has now come due. It is too late to avoid climate change, we are living with it now. What we badly need are governments and leaders with the character to implement the hard choices that are needed to minimise the harm societies will now face.

Chris Wright’s next book Organising Climate Change, is due out in late next year.

Image: Jo-Anne McArthur

Christopher Wright is Professor of Organisational Studies and leader of the Balanced Enterprise Research Network at the University of Sydney Business School. His research focuses on the diffusion of management knowledge, consultancy and organisational change.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.