SDGs by 2030 – are we on track?

Uncharted waters, protecting the young from online harms

Australia has some of the world’s strongest pool safety laws, with compulsory pool fencing specifications mandated to millimetre dimensions. Combined with compulsory swimming lessons in primary school, such rigour has seen Australia achieve a 67 percent reduction in drowning deaths in children under four across the last 30 years.

And yet, while we know young people are spending unprecedented amounts of time online, Australia is struggling to deliver a virtual ‘safety fence’ around online usage by adolescents.

I research young people’s engagement with the online world and the ways their behaviour enhances or undermines their wellbeing. It is clear that the amount of time many young people are spending online is detrimental to their wellbeing and is displacing other really important activities they need to undertake to build their confidence and their sense of connection with the community.

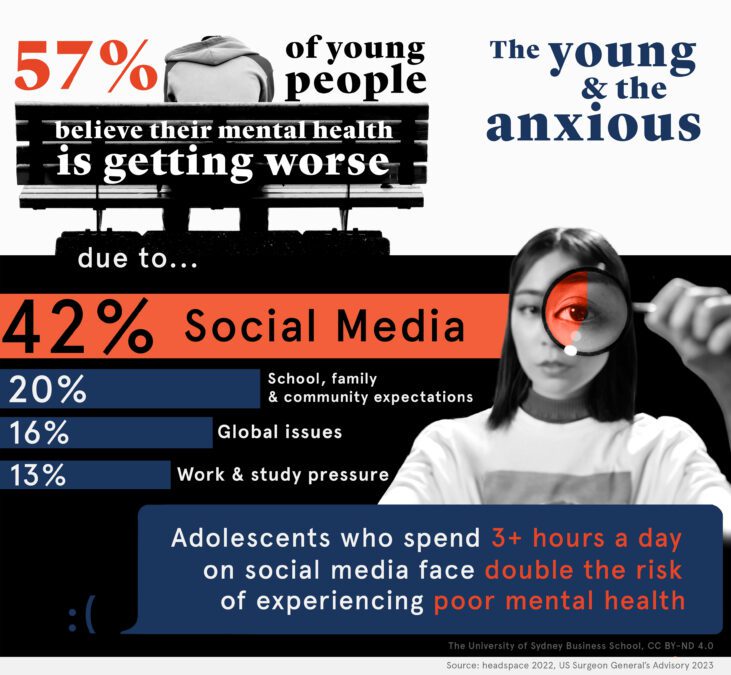

The other part of the online risk is what young people are doing while they are there. Rates of adolescent anxiety and depression are tracking in the wrong direction and the big risk is teen suicides. Research conducted and assembled by US social psychologist Jonathan Haidt is starting to show the links between adolescent social media use, particularly among girls, predicting greater anxiety and depression and a deterioration in mental health.

For girls, the general pattern is that their engagement with social platforms such as Instagram and Tik Tok heightens their concerns around body image and this consciousness is harming their mental health. For boys, the issue lies in the gaming space and the amount of time they’re spending online which is displacing physical activity – but also progress with their studies.

We know the adolescent brain is highly plastic and the ability to self-regulate and override impulses is not fully developed. For children, popular online spaces such as TikTok, Snapchat, and many games are designed to deliver massive dopamine hits that their brains have real trouble handling: they struggle to disconnect, and when they do, this delivers a huge hit to how they feel (as with any addiction). Just as we wouldn’t let a toddler play around a pool unsupervised, we need to regulate young peoples’ online access. And yes, there was vehement opposition to many of the pool regulations we now accept as sensible safety interventions. The data clearly tells us that the benefits of regulation plus education far outweigh the costs.

In the same way that water safety requires action from governments, schools and parents, erecting an effective cyber ‘safety fence’ will require action – both regulatory and educational – from the same three stakeholders. All-to-often, there is a significant gap between parents’ understanding of the risks, and the downstream impacts of the kind of unfettered access granted to many young children. Crucially, our own research shows that nothing psychological or even social, predicts young people’s addictive online behaviour. All the indicators point to the issue of access as being key. Parents need to be made aware the decisions they make regarding the access their five- year-old has to the online world will, ten years later, impact how the 15-year-old in their family feels and behaves. We need to help parents proactively set the boundaries, to have helpful conversations with their children, and to support them in putting up guard rails in the home.

Schools also need to build firm barriers. Children are not allowed to sit in class with a pet on their lap because it’s recognised this would be a massive distraction. Allowing mobile phones in class raises the same issue: it’s the basics of attention regulation. Trying to do two complex tasks at once (e.g., typing a message and listening to someone in a classroom) is very cognitively demanding. Studies show that complex muti-tasking like this generates a big ‘tax’ on our brain’s capacity to sustain attention and retain information. Keeping mobile phones out of the classroom, and even from the school yard, will make a difference to children’s learning and also to the development of inter-person social skills. Initial evidence suggests that schools in Australia that have adopted policies removing phone access during the school day are reaping the rewards in greater student social and physical activity with their peers.

In Australia the E-Safety Commissioner is going after companies such as X, Apple and Google, to hold them more accountable for the kinds of access and content they provide. No one wants to be accused of establishing a “thought police” regime, so it’s a balancing act between providing information to parents and also following the data to enact laws both within the school system and beyond in the best interests of our young people.

Australia’s E-Safety Commission is doing good work but is confronting significant resistance. And they are getting almost nowhere with the big tech companies. What’s required is a combined effort, as was shown with water safety, of government action and, most crucially, educating parents on how to protect the children in their care from the unintended harms of the online world.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target addressed:

Target 3.4 By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being.

Resources

Given the complexities of the online world, how should we best regulate children’s access to social media?

What evidence-informed strategies should parents follow in providing guard-rails for their children’s online access?

Articles

- Chang, M. L., & Lee, I. O. (2024). Functional connectivity changes in the brain of adolescents with internet addiction: A systematic literature review of imaging studies. PLOS Mental Health, 1(1), e0000022.

- Donald, J. N., Ciarrochi, J., & Guo, J. (2022). Connected or cutoff? A 4-year longitudinal study of the links between adolescents’ compulsive internet use and social support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 01461672221127802.

- Donald, J. N., Ciarrochi, J., & Sahdra, B. K. (2022). The consequences of compulsion: A 4-year longitudinal study of compulsive internet use and emotion regulation difficulties. Emotion, 22(4), 678.

- Donald, J. N., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P. D., & Sahdra, B. K. (2019). Compulsive internet use and the development of self‐esteem and hope: A four‐year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality, 87(5), 981-995.

- Firth, J., Torous, J., Stubbs, B., Firth, J. A., Steiner, G. Z., Smith, L., & Sarris, J. (2019). The “online brain”: how the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 119-129.

- Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, et al. Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? The American Psychologist 1998; 53:1017–1031.

- Subrahmanyam K, Kraut RE, Greenfield PM, et al. The impact of home computer use on children’s activities and development. The Future of Children/Center for the Future of Children, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation 2000; 10:123–144.

- Riehm, KE., MS., Feder KA., Tormohlen, KN., MPH., et al. (2019) Associations Between Time Spent Using Social Media and Internalizing and Externalizing Problems Among US Youth. JAMA Network, 76(12):1266-1273.

Websites

James is a Senior Lecturer (Teaching and Research) in the in Work and Organisational Studies discipline at the University of Sydney Business School, where he teaches management and leadership.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.