SDGs by 2030 – are we on track?

The business case for identifying and eliminating hazardous chemicals

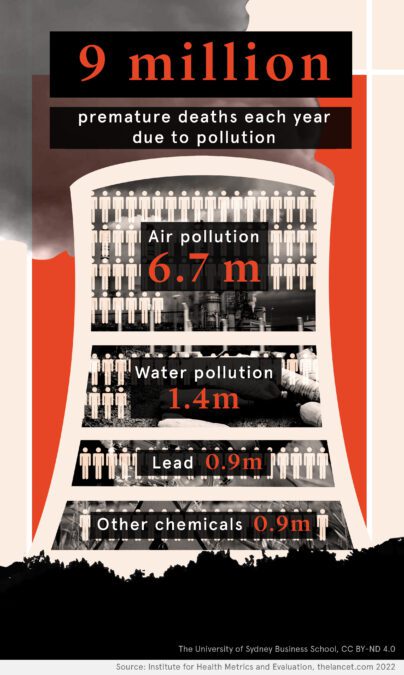

Chemical contamination is an incredibly serious problem impacting human health. At least two million people die every year due to chemical contact. Millions more suffer lifelong injuries such as brain damage, reproductive problems, allergies, and asthma. Chemical pollution also threatens the healthy functioning of the world’s ecosystems.

There are more than 40,000 intentionally produced chemical substances in commerce, with many more substances generated as unintentional by-products of industrial systems. Synthetic chemicals pervade the vegetables and meat we eat, the water we drink and swim in, the air we breathe. They are also present in many everyday products in our homes (e.g. cleaning agents, pest control products, carpeting, plastic toys).

Not all synthetic chemicals are toxic, and regulatory systems generally deliver safe outcomes. Nonetheless, the science underpinning conclusions of safety about substances in commerce does shift (e.g. DDT in the 1960s; BPA and PFAS more recently) and regulators are increasingly challenged. Data about the health and environmental effects of most substances is by and large absent.

Target 3.9 within SDG 3 aims to substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals as well as the chemical contamination in our air, water and soil.

I study innovation and science commercialisation as they happen in real time. My research focuses on new technologies for chemicals management. I undertake engaged innovation research, including with regulators at Health Canada, and Environment and Climate Change Canada. We embed postdoctoral research fellows and PhD students into inventing teams of natural scientists, engineers and biomedical researchers who are developing new technologies for chemical risk assessment.

The scientists I collaborate with in Canada are working on a leading-edge genomics-based technology – EcoToxChips – to quickly test for toxicity and at low cost. Their toxicity testing is conducted more ethically than incumbent methods as it does not involve animal deaths.

I and other Business School researchers mobilise knowledge about innovation and entrepreneurship in a timely manner, to help the technical experts in the team to stay on track and focused. Sometimes their initial vision can be too ambitious, involving multiple use cases for the technology. We introduce a design thinking mindset and methodology to projects. Taking a customer focus puts the end users at the core of technology development, testing and validation. The EcoToxChip, for example, can be used by business, regulators and academics to identify, prioritise and manage environmental chemicals in species and their environments.

There is a strong business case for improved chemicals management. Air pollution alone costs $8.1 trillion annually, 6.1 percent of global GDP. For individual companies, managing the health and environmental risks of chemicals in their supply chains, production processes, and end products is good business because these can become legal and reputational risks to companies through a process termed ‘risk translation’. Superior chemicals management is therefore a form of insurance. And it is responsible. The ultimate goal is to have human bodies and ecosystems free of toxic substances.

Scientists are working hard on these problems – but there are no environmental or health benefits from their work until these technologies are commercialised and implemented at scale. This is where business school research adds value.

Business schools are an under-mobilised resource that could be better leveraged to help deliver superior commercialization outcomes quicker. And unlike private consultants, academics don’t hoard the information – we publish lessons learnt in publicly available journals. We bring an academic mission to innovation and entrepreneurship.

I’d like to see more people doing engaged innovation research, and I’d love to see more government funding to build multidisciplinary teams to get promising inventions out of the lab and into society sooner. Business school research can help universities to deliver more positive impact, sooner.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target addressed:

Target 3.9 By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination.

Resources

Books

- Maguire, S. & Hardy, C., 2019, “The discourse of risk and processes of institutional change: The case of green chemistry”. In Reay, T. & Zilber, T. (eds.), Institutions and Organizations: A Process View: Perspectives on Process Organization Studies, Volume 9. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 154 – 173.

- Hardy, C. & Maguire, S., 2019, “The Janus Faces of Risk”. In Gephart, R., Miller, C., Svedberg Helgesson, K. (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Risk, Crisis and Emergency Management, Routledge, Oxford, UK, 504 – 507.

- Maguire, S. & Hardy, C., 2016, “Riskwork: three scenarios from a study of industrial chemicals in Canada”. In Power, M. (ed.), Riskwork. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 130 – 139.

- Maguire, S., Iles, A., Matus, K., Mulvihill, M., Schwarzman, M.R., Wilson, M.P., 2013, “Bringing Meanings to Molecules by Integrating Green Chemistry and Social Sciences”, in International Social Science Council (ed.), World Science Report 2013: Changing Global Environments: Transformative Impact of Social Sciences, UNESCO, Paris, France, 298 – 303.

- Maguire, S., 2008, “Contested Icons: Rachel Carson and DDT”, in Sideris, L. & Moore, K.D. (eds.), On Nature’s Terms: the Legacy and Challenge of Rachel Carson, SUNY Press, New York, NY, 194-214.

Academic papers

- Crump, D., Hickey, G., Boulanger, E., Masse, A., Head, J.A., Hogan, N., Maguire, S., Xia, J., Hecker, M., Basu, N. 2023. “Development and initial testing of EcoToxChip, a novel toxicogenomics tool for environmental management and chemical risk assessment”. Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry. 42(8): 1763 – 1771.

- Daymond, J., Knight, E., Rumyantseva, M., & Maguire, S. 2023. “Managing ecosystem emergence and evolution: Strategies for ecosystem architects”. Strategic Management Journal. 44(4): O1 – O27.

- Mondou, M., Hickey, G., Rahman, H.M.T., Pain, G., & Maguire, S. 2022. “Policy Forums and Learning in Fields Underpinned by Regulatory Science”. Environmental Science & Policy. 137: 349 – 358.

- van der Vegt, R., Maguire, S., Crump, D., Hecker, M., Basu, N., & Hickey, G. 2022. “Chemical Risk Governance: Exploring Stakeholder Participation in Canada, the USA, and the EU”. Ambio. 51. 1698 – 1710.

- Soufan, O., Ewald, J., Zhou, G., Hacariz, O., Boulanger, E., Alcaraz, A., Hickey, G., Maguire, S., Pain, G., Hogan, N., Hecker, M., Crump, D., Head, J., Basu, N. & Xia, J. 2022. “EcoToxXplorer: leveraging design thinking to develop a standardized web-based transcriptomics analytics platform for diverse users”. Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry. 41(1) 21 – 29.

- Pokrajac, L., Abbas, A., Chrzanowski, W., Dias, G., Eggleton, B., Maguire, S., Maine, E., Malloy, T., Nathwani, J., Nazar, L., Sips, A., Sone, J., van den Berg, A., Weiss, P., & Mitra, S. 2021. “Nanotechnology for a Sustainable Future: Addressing Global Challenges with the International Network4Sustainable Nanotechnology”. ACS Nano. 15(12): 18608–18623.

- Mondou, M., Maguire, S., Pain, G., Crump, D., Hecker, M., Basu, N. & Hickey, G. 2021. “Envisioning an International Validation Process for New Approach Methodologies in Chemical Hazard and Risk Assessment”. Environmental Advances. 4: 100061.

- Tong, A. et al. 2021. “Research Priorities for COVID-19 Sensor Technology”. Nature Biotechnology.

- Pain, G., Hickey, G., Mondou, M., Crump, D., Hecker, M., Basu, N., Maguire, S. 2020. “Drivers and Obstacles to the Adoption of Toxicogenomics for Chemical Risk Assessment: Insights from Social Science Perspectives”. Environmental Health Perspectives. In press.

- Hardy, C., Maguire, S., Power, M., Tsoukas, H. 2020. “Organizing Risk: Organization and Management Theory for the Risk Society”. Academy of Management Annals. 14(2): 1032 – 1066.

- Mondou, M., Hickey, G., Pain, G., Maguire, S., Crump, D., Hecker, M., Basu, N. 2020. “Factors affecting the perception of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) in the ecotoxicology community”. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 16(2): 269 – 281.

- Hardy, C. & Maguire, S., 2020. “Organizations, Risk Translations and the Ecology of Risks: The Discursive Construction of a Novel Risk”, Academy of Management Journal, 63(3): 685 – 716.

- Basu, N., Crump. D., Head, J., Hickey, G., Hogan, N., Maguire, S., Xia, J., Hecker, M. 2019, “EcoToxChip – A Next-Generation Toxicogenomics Tool for Chemical Prioritization and Environmental Management”. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 38(2): 279 – 288.

- Hardy, C. & Maguire, S., 2016. “Organizing Risk: Discourse, Power and Riskification”. Academy of Management Review, 41(1): 80 – 108.

- Finalist for 2016 Academy of Management Review Best Paper Award.

- Maguire, S. & Hardy, C., 2013, “Organizing Processes and the Construction of Risk: A Discursive Approach”. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1): 231 – 255.

- Kisfalvi, V. & Maguire, S., 2011, “On the Nature of Institutional Entrepreneurs: Insights from the Life of Rachel Carson”. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(2): 152 – 177.

- Hardy, C. & Maguire, S., 2010, “Discourse, Field-configuring Events, and Change in Organizations and Institutional Fields: Narratives of DDT and the Stockholm Convention”. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1365 – 1392.

- Maguire, S. & Hardy, C., 2009, “Discourse and Deinstitutionalization: The Decline of DDT”. Academy of Management Journal, 52(1): 148-178.

- reprinted as a book chapter, Maguire & Hardy, 2011 (see below).

- Maguire, S. & Hardy, C., 2006, “The Emergence of New Global Institutions: A Discursive Perspective”. Organization Studies, 27(1): 7-29.

- reprinted as a book chapter, Maguire & Hardy, 2012 (see below).

- Maguire, S. & Ellis, J., 2005, “Redistributing the Burden of Scientific Uncertainty: Implications of the Precautionary Principle for State and Non-state Actors”. Global Governance, 11(4): 505-526.

- Maguire, S., 2004, “The Coevolution of Technology and Discourse: A Study of Substitution Processes for the Insecticide DDT”. Organization Studies, 25(1): 113-134.

- Maguire, S. & Ellis, J., 2003, “The Precautionary Principle and Global Chemical Risk Management: Some Insights from the Case of Persistent Organic Pollutants”. Greener Management International: The Journal of Corporate Environmental Strategy and Practice, 41: 33-46.

Websites

- Silent Spring

- Our Stolen Future

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Confirmed cases of Malaria

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation: Global Burden of Disease

- The Lancet

- National Library of Medicine: Number of HIV/AIDS cases

- National Library of Medicine: Numbers for interpersonal violence

- Our World in Data: Annual death from road accidents

- Our World in Data: Deaths by risk factor

- Our World in Data: Tuberculosis death rate

Professor Steven Maguire is Deputy Dean (Research) at the University of Sydney Business School since January 2024. An important stream of his research focuses on technological and institutional change driven by the emergence of new risks to human health and the environment, theorizing the role of non-market actors in shaping the adoption or abandonment of particular technologies.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.