Christopher Wright

SDGs by 2030 – are we on track?

Saving the planet requires decarbonising energy

Offshore wind farms towering over remote oceans, solar panels perched across a landscape of suburban roofs or tapping into the geothermal energy in the world’s ‘hot rocks’ – upbeat stories about the rise of renewable energy sources are offering hope of a sustainable future amid endless economic growth.

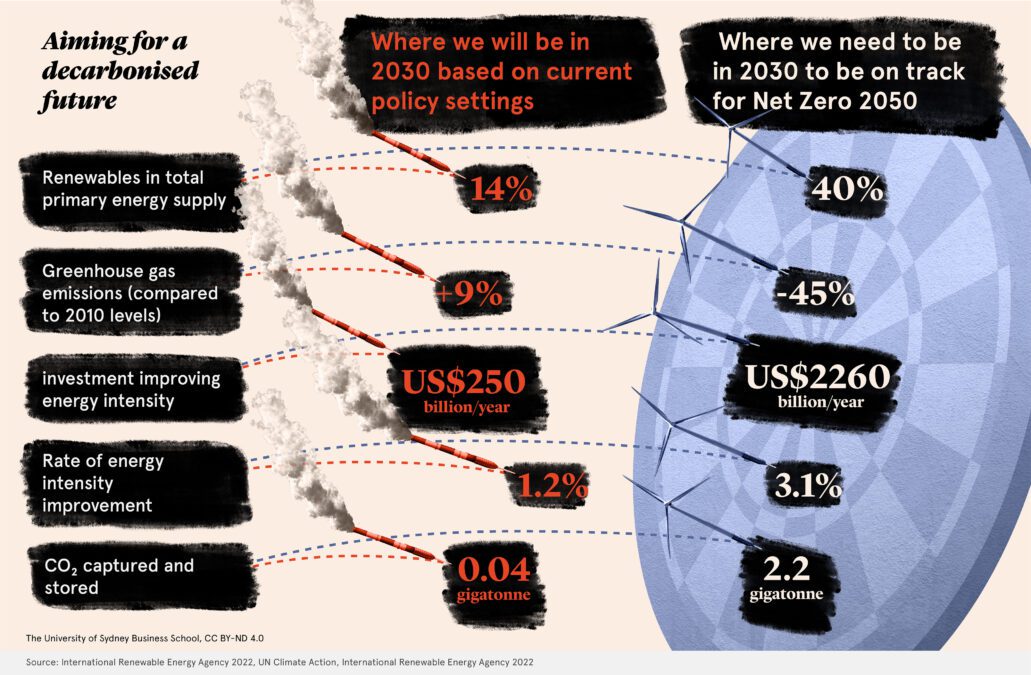

However, the world still relies upon fossil fuel-based energy for more than 80 per cent of its needs. This is roughly the same proportion as 50 years ago.

Despite the uptake of renewable energy, greenhouse gas emissions continue to grow, driven by expanding consumption and the world’s demand for compound economic growth.

Also unchanged is the predominant economic system, which relies on fossil fuel consumption.

While SDG 7 targets aim to achieve affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all by 2030, the broader SDGs do not confront the economic and political dominance of fossil fuels. Nor do they tackle the most pressing issue facing humanity: climate change.

The world’s leading petro-states, including the United States, China, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Australia, continue to expand their production and consumption of fossil fuels. Increasing investment in renewable energy, while significant, has simply supplemented the growing energy demands of the globalised economy.

The world’s energy production and consumption need to be radically decarbonised.

Targets to get there include an honest price on carbon pollution, the end of fossil fuel subsidies, major incentives for renewable energy investment, the nationalisation of energy production and distribution and the prohibition of new coal, oil, and gas projects.

Making the shift to more equitable energy consumption between rich and poor nations also requires the selective degrowth of economic sectors. Ensuring people have sufficient energy to live a sustainable existence while radically decarbonising energy production and consumption by the energy profligate requires nothing less than a reinvention of the global economy. However, such a transition has been denied and delayed by the political capture of governments by the fossil fuel sector.

At a time of worsening climate impacts, the innovative capacities of industry have focused, paradoxically, on more efficient ways to extract and use fossil fuels. This fossil fuel hegemony has been maintained in the face of a growing social movement for climate action.

Corporations have transformed the grand challenge of climate change into a ‘no worries’ version of business as usual. Managers make sense of the climate crisis in terms of their identities and emotions. To avoid the coming global catastrophe, citizens need to use their identities (youth activist, employee agitator, community organiser), political agency and their informed emotions to confront and upend business as usual.

The survival of our world depends on it.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets addressed:

Target 7.1 By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services

Target 7.2 By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix

Target 7.3 By 2030, double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency

Resources

Student assignment

Try to imagine a world in which fossil fuels have been replaced by renewable energy. What would such a world look like and how would it differ from our current reality?

Further reading

Books

- Christopher Wright, Daniel Nyberg (2015) Climate Change, Capitalism and Corporations: Processes of Creative Self-Destruction. Cambridge University Press.

- Daniel Nyberg, Christopher Wright, Vanessa Bowden (2023) Organising Responses to Climate Change: The Politics of Mitigation, Adaptation and Suffering . Cambridge University Press.

Article

- Wright, C., & Nyberg, D. (2017). An inconvenient truth: How organizations translate climate change into business as usual. Academy of Management Journal, 60(5), 1633-1661.

Podcasts

Websites

Christopher Wright is Professor of Organisational Studies and leader of the Balanced Enterprise Research Network at the University of Sydney Business School. His research focuses on the diffusion of management knowledge, consultancy and organisational change.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.