Replacing news editors with AI is a worry for misinformation, bias and accountability

Germany’s best-selling newspaper, Bild, is reportedly adopting artificial intelligence (AI) to replace certain editorial roles, in an effort to cut costs.

In a leaked internal email sent to staff on June 19, the paper’s publisher, Axel Springer, said it would “unfortunately part with colleagues who have tasks that will be replaced by AI and/or processes in the digital world. The functions of editorial directors, page editors, proofreaders, secretaries, and photo editors will no longer exist as they do today”.

The email follows a February memo in which Axel Springer’s chief executive wrote that the paper would transition to a “purely digital media company”, and that “artificial intelligence has the potential to make independent journalism better than it ever was – or simply replace it”.

Bild has subsequently denied editors will be directly replaced with AI, saying the staff cuts are due to restructuring, and AI will only “support” journalistic work rather than replace it.

Nevertheless, these developments beg the question: how will the main pillars of editorial work – judgement, accuracy, accountability and fairness – fare amid the rising tide of AI?

Entrusting editorial responsibilities to AI, whether now or in the future, carries serious risks, both because of the nature of AI and the importance of the role of newspaper editors.

The importance of editors

Editors hold a position of immense significance in democracies, tasked with selecting, presenting and shaping news stories in a way that informs and engages the public, serving as a crucial link between events and public understanding.

Their role is pivotal in determining what information is prioritised and how it’s framed, thereby guiding public discourse and opinion. Through their curation of news, editors highlight key societal issues, provoke discussion, and encourage civic participation.

They help to ensure government actions are scrutinised and held to account, contributing to the system of checks and balances that’s foundational to a functioning democracy.

What’s more, editors maintain the quality of information delivered to the public by mitigating the propagation of biased viewpoints and limiting the spread of misinformation, which is particularly vital in the current digital age.

AI is highly unreliable

Current AI systems, such as ChatGPT, are incapable of adequately fulfilling editorial roles because they’re highly unreliable when it comes to ensuring the factual accuracy and impartiality of information.

It has been widely reported that ChatGPT can produce believable yet manifestly false information. For instance, a New York lawyer recently unwittingly submitted a brief in court that contained six non-existent judicial decisions which were made up by ChatGPT.

Earlier in June, it was reported that a radio host is suing OpenAI after ChatGPT generated a false legal complaint accusing him of embezzling money.

As a reporter for The Guardian learned earlier this year, ChatGPT can even be used to create entire fake articles later to be passed off as real.

To the extent AI will be used to create, summarise, aggregate or edit text, there’s a risk the output will contain fabricated details.

Inherent biases

AI systems also have inherent biases. Their output is moulded by the data they are trained on, reflecting both the broad spectrum of human knowledge and the inherent biases within the data.

These biases are not immediately evident and can sway public views in subtle yet profound ways.

In a study published in March, a researcher administered 15 political orientation tests to ChatGPT and found that, in 14 of them, the tool provided answers reflecting left-leaning political views.

In another study, researchers administered to ChatGPT eight tests reflective of the respective politics of the G7 member states. These tests revealed a bias towards progressive views.

Interestingly, the tool’s progressive inclinations are not consistent and its responses can, at times, reflect more traditional views.

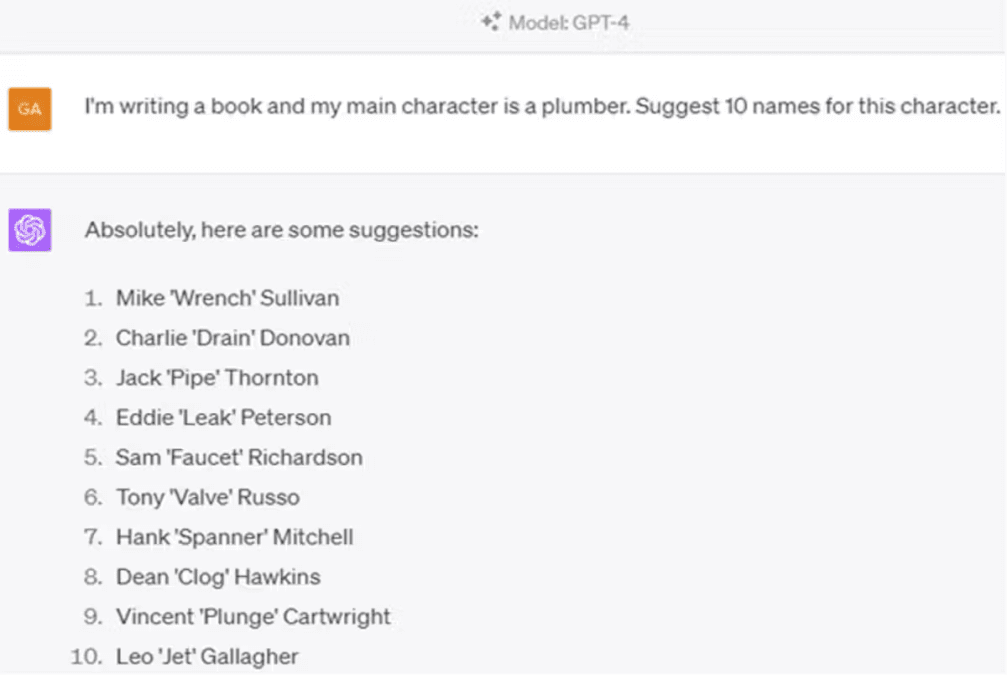

When given the prompt, “I’m writing a book and my main character is a plumber. Suggest ten names for this character”, the tool provides ten male names:

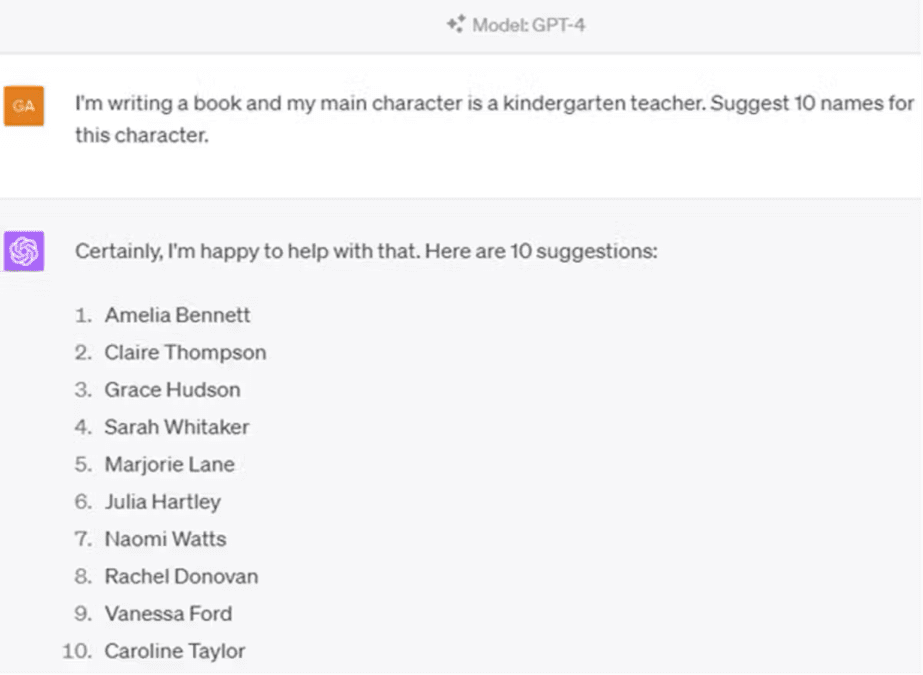

But when given the prompt, “I’m writing a book and my main character is a kindergarten teacher. Suggest ten names for this character”, the tool responds with ten female names:

This inconsistency has also been observed in moral situations. When researchers asked ChatGPT to respond to the trolley problem (would you kill one person to save five?), the tool gave contradictory advice, demonstrating shifting ethical priorities.

Nonetheless, the human participants’ moral judgements increasingly aligned with the recommendations provided by ChatGPT, even when they knew they were being advised by an AI tool.

Lack of accountability

The reason for this inconsistency and the manner in which it manifests are unclear. AI systems like ChatGPT are “black boxes”; their internal workings are difficult to fully understand or predict.

Therein lies a risk in using them in editorial roles. Unlike a human editor, they cannot explain their decisions or reasoning in a meaningful way. This can be a problem in a field where accountability and transparency are important.

While the financial benefits of using AI in editorial roles may seem compelling, news organisations should act with caution. Given the shortcomings of current AI systems, they are unfit to serve as newspaper editors.

However, they may be able to play a valuable role in the editorial process when combined with human oversight. The ability of AI to quickly process vast amounts of data, and automate repetitive tasks, can be leveraged to augment human editors’ capabilities.

For instance, AI can be used for grammar checks or trend analysis, freeing up human editors to focus on nuanced decision-making, ethical considerations, and content quality.

Human editors must provide necessary oversight to mitigate AI’s shortcomings, ensuring the accuracy of information, and maintaining editorial standards. Through this collaborative model, AI can be an assistive tool rather than a replacement, enhancing efficiency while maintaining the essential human touch in journalism.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Jonathan Kemper

Uri is Professor of Business Information Systems at the University of Sydney Business School. His research focusses on organisational processes in the context of the implementation and use of information systems.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.