Marcus Carter and Ben Egliston

All work and no play in the future of virtual reality

Head-Mounted Virtual Reality (VR) is generally discussed as a gaming technology, praised for its capacity to simulate experiences that are psychologically real. Think, Ready Player One or Star Trek’s Holodeck. However for Facebook (who hold a dominant 39% share of the VR market) VR is not simply a gaming device but – as we unpack in our research a new frontier for social media, framed by Zuckerberg as a “new kind of social computing platform.”

Treating VR as a gaming technology only grossly underestimates its potential impact on society. Modern VR devices are extractive digital sensors capable of rendering the body in such granular detail that your use of a VR headset is likely biometric: a term from computer security that refers to personal data that is derived from our unique behavioural or physical characteristics, which can then be used to confirm our identity, or track us more accurately. What we do in VR, how we look, and how we react, offers unparalleled insights into our cognition that we’re only just beginning to understand.

While this might be a mundane concern in the context of your performance at the lightsaber music game Beat Saber, VR is increasingly being adopted as a tool in workplaces. Walmart has been promoting employees based (in part) on performance at VR tasks since 2019. In September 2020, Facebook introduced ‘Infinite Office‘ – a vision for a PC experience fully enclosed by Facebook’s platform – and a video of Japanese grocery store FamilyMart’s VR-controlled robot stocking shelves recently went viral.

These possible futures for VR bring with them the enormous risks we have already seen in the use of algorithms, data analytics and automated decision making in other contexts, such as the Federal Government’s ‘Robodebt’ scheme and the use of facial recognition in policing in the United States. While VR can generate vast quantities of data, it is not objective or free of bias. As Lisa Gitelman and Virginia Jackson put it, data is never raw. It is always “cooked” — collected, stored, and circulated with particular aims and logics in mind.

The possible benefits of VR– in contexts like education, training and for socialising – run the risk of being dangerously outweighed by the technology’s potential for surveillance and control. We must be asking these technology companies and their proponents about the adoption of VR as a work platform; how might these types of ‘employee productivity’ tracking and analytics apparatus being advanced in workplaces like Amazon warehouses and through software suites like Microsoft 365 be expanded – to the detriment of employees? What disabilities, cultural differences and backgrounds will become codified behind the black-box of algorithmic bias? How will the hyper flexibility of VR-telerobots expand the gig-economy into new domains?

Measures of oversight for VR technologies are still nascent, but include the Extended Reality Safety Initiative, a non-profit initiative scoped around data privacy, as well as industry standards groups. Broad data privacy laws – such as the European General Data Protection Regulation and the California Consumer Privacy Act – provide some regulatory oversight (although are limited in their applicability to the use of VR in the workplace, and do not attempt to limit extractive power, rather to create clearer mechanisms for consent and transparency in data use). More general efforts to militate against technological surveillance in spaces like the workplace are clear through worker unionisation (such as Amazon) which increasingly pushes back against surveillance, and unionisation in the tech sector is pushing back against the development of surveillant technologies.

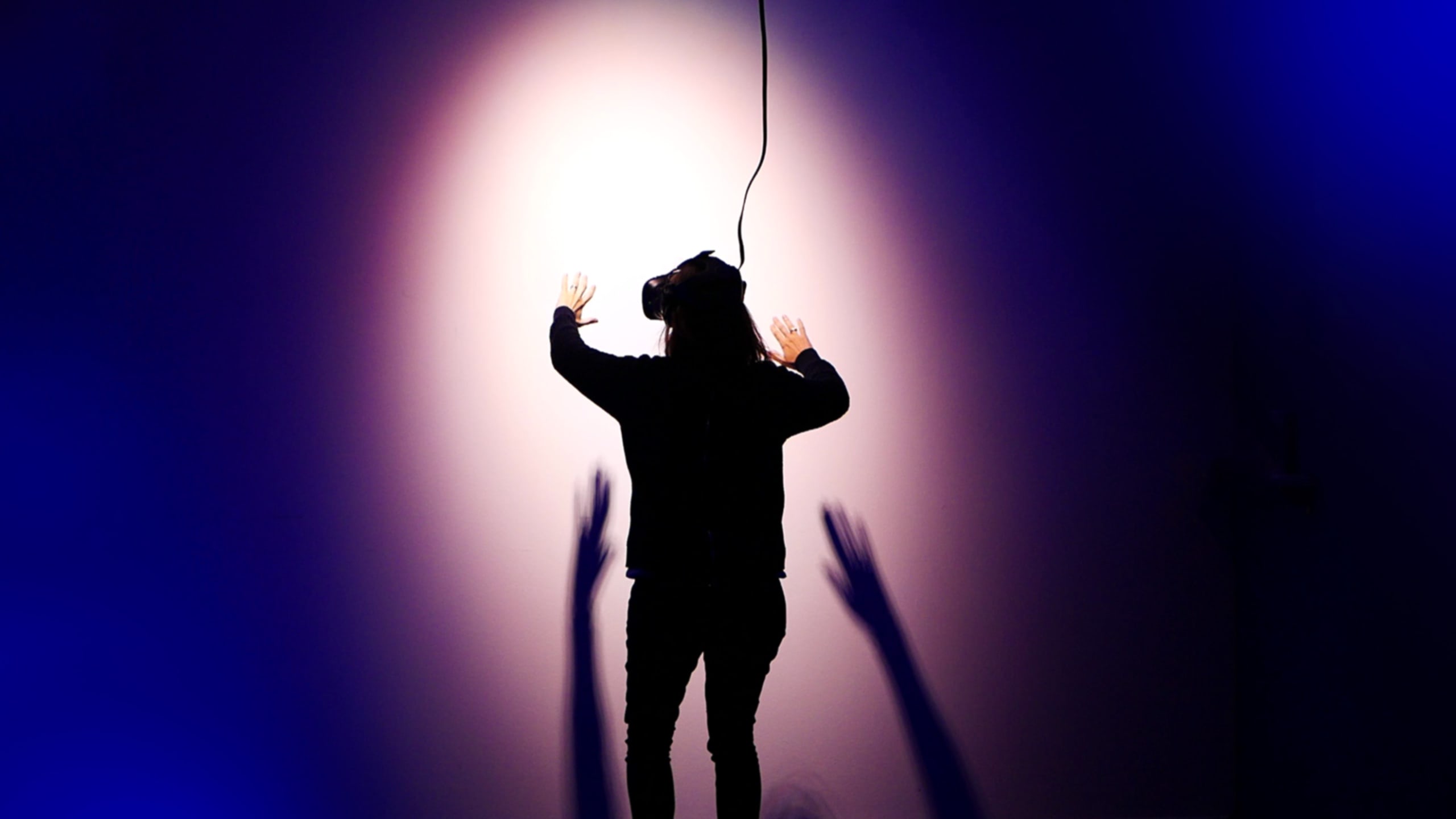

Image: Stella Jacob

Marcus is a Senior Lecturer in Digital Cultures at The University of Sydney, and a recipient of the University’s SOAR fellowship in 2018.

Ben is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Digital Media Research Centre at Queensland University of Technology.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.