SDGs by 2030 – are we on track?

Australia is meeting the education targets, but on the cheap

To the rest of the world Australia has an enviable education system. Across all four tiers of education Australia could be said to be meeting the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 target of providing quality education.

However, we have done so by sweating legacy assets established over decades (especially in our universities and vocational education system) and exhausting the goodwill of the teacher workforce. This cannot hold.

Historically teachers in Australia enjoyed secure work and sustainable salaries. Over the last 30 years there has been an erosion in the quality of teaching work. Fixed and casual employment is widespread, especially for young educators. Successive government policies capping public sector wages has supressed teacher pay while their work intensity has soared. Ask your teacher friends and relatives how stressed they are daily coping with integrating new technologies into the classroom, pupil behaviour and out-of-hour student (and parental) demands. It won’t be a happy conversation.

Australia’s educational achievements are in a precarious state and advances are being undermined by a lack of investment in essential infrastructure – especially our educators. The table (available here) provides a summary of key developments since 2015.

On the face of it the early childhood sector is a ‘success’ story, with a 11.4 percent rise in enrolments since the start of the SDGs. This was supported by a 38 percent increase in government funding ($2.6 billion) between 2015 to 2022. However, the majority of the public investment in early childhood education has flowed into for-profit operators who now provide 70 percent of centre-based day care places. A recent review found this sector marred by high costs to parents and significant variations in the geographic availability and quality of services.

At the same time early childhood teachers labour under the lowest pay. Consequently, the entire system is stressed by a dire shortage of teachers. The sector has one of the largest proportions of unfilled vacancies for any Australia occupation: pre-school educators are the top occupation where vacancies outstrip applicants in the greater Sydney region (Seek 2024).

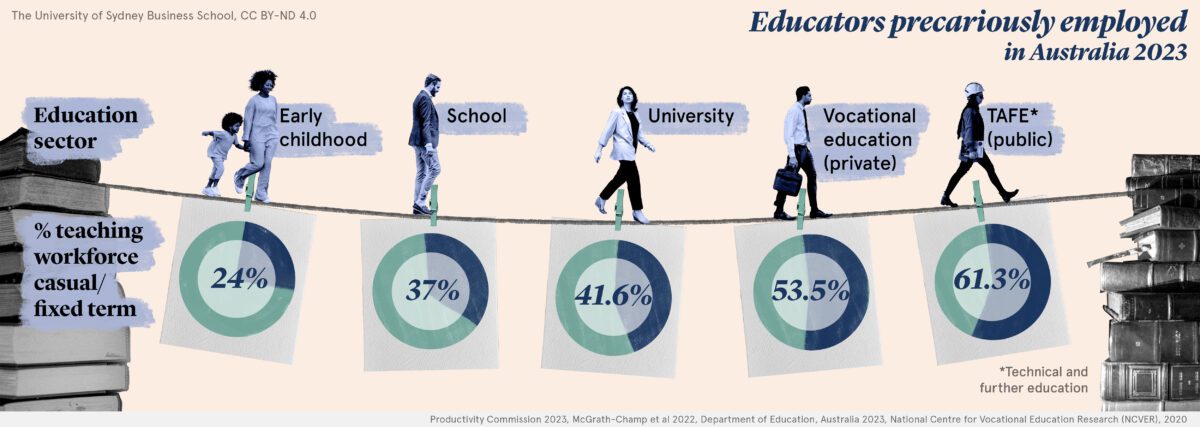

In high schools the system is failing its most vulnerable students. The proportion of pupils transitioning from year 10 to year 12 fell by more than 4 percent between 2015 and 2023, a period when government policy was supposed to raise the school completion rate. In addition, a decade of wage suppression has contributed to high numbers of teachers leaving the profession. Rising work pressures – teachers have one of the highest levels of workers compensation claims for psychological injury – also contribute this situation. Casual and fixed term employment account for over a third (37 percent) of school teaching positions in NSW, contributing to a dysfunctional labour market in school education. The term ‘burnout’ does not adequately express the daily experience of this cohort struggling to cover lessons for absent colleagues.

The vocational education sector is supposed to fulfil two main tasks: training

the ‘on the tools’ workforce and offering ‘second chance’ learning to people who did not like school or who have otherwise not participated in Australia’s high schools – migrants, refugees, school refusers and other disadvantaged groups.

Once a shining example of diligent community service, our technical and further education system has been commercialised. The attempt to turn vocational education into a profit-making enterprise has seen teacher standards undermined. The number of people earning higher level vocational qualifications (the level of study that prepares people for good jobs as diploma level engineers and care workers) fell by more than 9,000 between 2015 and 2020. And employers are not picking up this responsibility. The proportion of employees reporting employer-provided training fell by more than 3 percent between 2013-2021, to just 23 percent. In the meantime, more than 61 percent of teachers in the public vocation training system are either casual or fixed term employees.

The elite higher education system faces similar challenges. Universities now rely heavily on casual and fixed-term staff, with tenured academics comprising less than 60 percent of the faculty. The funding model is unsustainable, as government funding has dropped to 45.6 percent of total income. This shortfall has led universities to seek substantial funding from overseas students, whose numbers increased by 21.8 percent from 2015 to 2021. However, the reliability of this revenue is uncertain as Australia tightens immigration controls aimed at reducing overseas student numbers.

The most pressing challenge is to move beyond the great intellectual rigidity of our time: namely that quasi-market arrangements and corporate models of managerial accountability are the best way to organise domains like education. Research I have undertaken for the NSW Department of Education, UNESCO, the ILO, teacher unions and the Directors of Welsh Colleges of Further Education has identified more sustainable and effective ways forward for vocational education and the teaching profession in particular.

It is vital that greater respect and support is given to education as a domain and a profession. We need to recognise that the 40-year experiment with market inspired reform has failed. Preoccupation with ‘flexibility’ has distracted attention from the prerequisite for effective adaptive capacity: strong institutions supported by stable funding over time. Kattel and colleagues (2019) refer to this as ‘agile stability’.

Educational institutions should be nurtured to shape the labour market, not merely serve it. The challenge, along with its exciting opportunities, lies in building partnerships within the education sector and with economic and societal agents. These collaborations should focus on generating and sharing new knowledge for the benefit of all.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets addressed:

Target 4.1 By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes

Target 4.2 By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education

Target 4.3 By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university

Target 4.4 By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship

John is the Co-Director of the Mental Wealth Initiative and a Professor in the Business Information Systems Discipline at the University of Sydney Business School. John is an expert in labour market structuring and its implications for skills and education. Current research interests include the future of expertise and social solidarity in a world of mass underemployment and AI.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.